Some exposition, briefly: The Real Book is a fake book that was most likely compiled by anonymous Berklee students in the 1970s. It contains lead sheets for over a thousand songs across three handwritten volumes that went through 5 bootleg revisions before being legitimized as the “Sixth Edition” by Hal Leonard in 2003. Despite being 40 years old – and having been underground most of its life – it’s the most common fake book that I know of. You can find it at gigs, in high schools and colleges, at jam sessions, and in people’s homes for their personal practice and reference. I would guess that every “jazz” musician reading this has had access to a copy of The Real Book at some point.

Some people are against using fake books like The Real Book because people think they are a crutch, or a cheap ways to learn tunes, and books like The Real Book are frequently unwelcome at jam sessions because Come On Dude, Learn The Tune. I can’t argue with that last bit. It’s a bad look to read from a book at a public jam session, at least in New York City. But lead sheets are good for a number of reasons and I appreciate having them around. I am not out to convince anyone not to use fake books or lead sheets.

I am writing this to convince you to stop using The Real Book, specifically. The charts in the bootleg version – widely available on the internet and still very common in print form among musicians my age and older – are inconsistent, sloppy and frequently inaccurate. The legal Sixth Edition fixed many of these problems, but in doing so the new editors have made the Sixth Edition incompatible with older versions, and the Sixth Edition still contains more than a few questionably transcribed chord changes and melodies. It also does not include the lyrics of any tunes, so if you are working with a singer who also wants to read the tune, you’re going to need a different book anyway.

We’ll talk about the Sixth Edition in a bit. But first we need to address those bootleg editions. They are still everywhere, and we need to be done with them. The closest nonmusical analogy I can think of is if a imperfectly translated collection of poems became the standard versions of those poems in English, even though the original poems were also in English. Why would anyone want to use that book? And it’s not that The Real Book wanted to simplify songs for people to learn, like a Cliff’s Notes thing for musicians; in fact, the original Real Book’s charts were typically more complicated than the original tunes, sometimes in ways that were completely arbitrary.

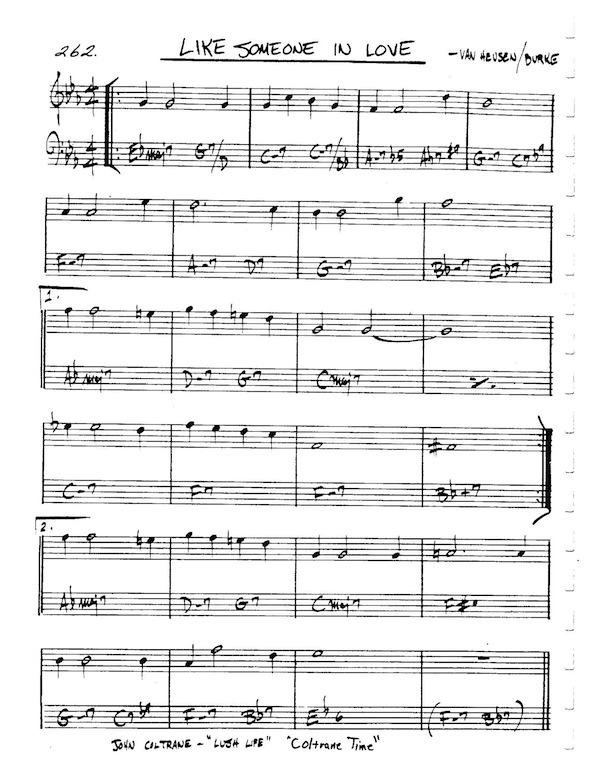

In some cases, a standard tune was presented in The Real Book with alternate chord changes in place of the original chord progression with no indication that they are alternate changes. This could pose a problem if someone was reading from the book while another person was playing or singing from memory, or if someone was using the book as a reference. Here is the chart for the Jimmy Van Heusen tune Like Someone In Love:

These are great chord changes, but they’re not the chord changes that Jimmy Van Heusen wrote. John Coltrane, I assume, created these alternate chord changes, which means this isn’t a very good reference for someone who wants to learn the song. Assuming the key of Eb major, measure six should be Bb7 followed by Bb+7, and measure 7 should be some form of Eb major. Those are the original chords of the song, and they are the chords that are most commonly played on recordings from the 1950s and 1960s. This is not to say that the altered chords are “wrong.” This is also not to say that people shouldn’t play alternate changes. But if a book is going to be the main book that people use, the original chords for a tune should be at the very least included, and any alternate chord changes should be indicated as such.

In other cases, the melody for an older standard was written out as someone might freely interpret it, instead of how it is was published, or how it generally thought to exist in its pure form. One example of this is Basin St. Blues, from the original Real Book Vol. 2:

This is a mess. I think someone playing this chart note-for-note could sound pretty swinging, but this is clearly not the melody for Basin Street Blues. It’s not even close. Whoever prepared this chart has done the interpreting for you, and it’s a very loose, boozy interpretation. As a reference it is pretty much useless: the rhythm doesn’t match the unprinted lyrics at all (e.g. the 4th measure of B) and there’s no indication that the A section is a call and response. For this chart to work, everyone on stage would have to already know the song. And if everyone already knows the song, they probably don’t need a chart.

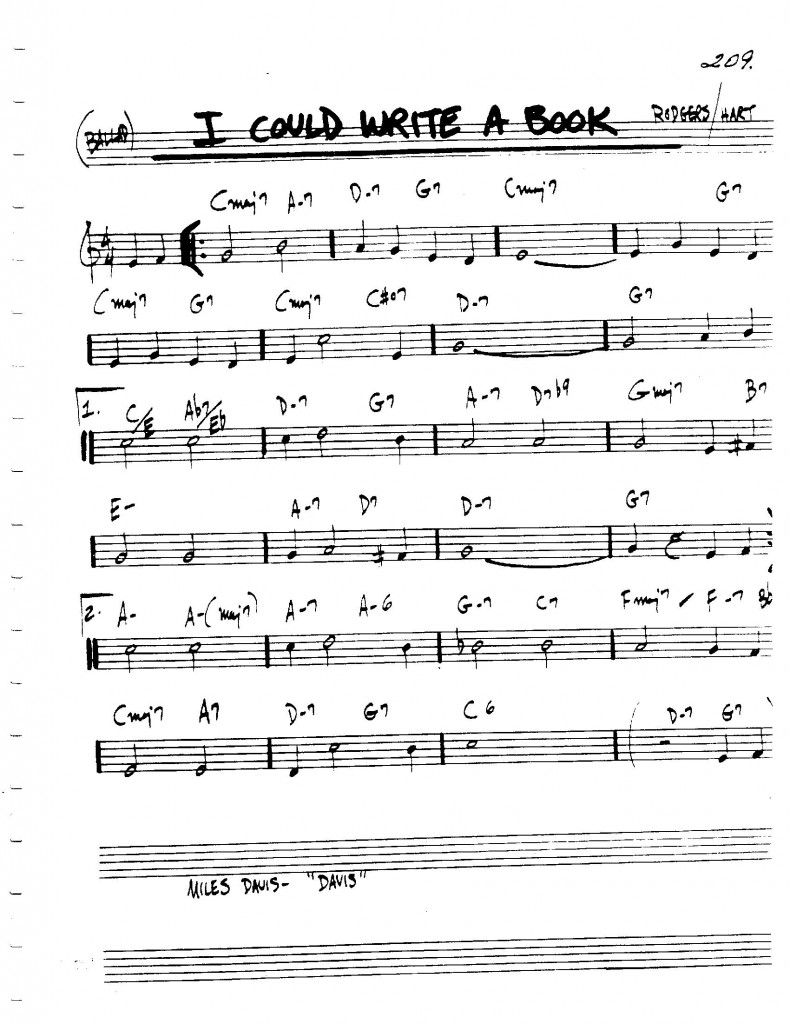

Not every older tune was embellished like this; a lot of standards and showtunes were transcribed in those bootleg Real Books with only minor deviations from their original melodies and original chord progressions. This does not mean that the charts are totally useful. Take Rodgers and Hart’s I Could Write A Book, from Pal Joey:

The tune is marked as a Ballad, but the song I Could Write A Book was written as a medium-tempo bounce, and it’s almost always played as a medium- or up-tempo swing. And even though it says I Could Write A Book is a ballad, the Real Book didn’t recommend any of the great ballad recordings of the tune; instead it recommended a single recording: the Miles Davis recording from his Prestige years, which was recorded at a pretty fast tempo. This tune is a great ballad, and a great burner, and a great mid-tempo tune, but it doesn’t do anyone any good to call a tune a ballad and recommend an uptempo recording on the same page.

It would be understandable that a book written by jazz musicians would have mistakes or inconsistencies when it comes to the old popular standards and showtunes. But The Real Book didn’t just get the old standards wrong. It got many “jazz standards” written by jazz musicians wrong, too. A perfect example of this Blue Train, or “Blue Trane,” as it was famously mis-titled in the Real Book. Blue Train is the title track of one of the most enduring LPs of its era. Here is its page from the bootleg The Real Book:

Here is the original recording:

It shouldn’t take a seasoned musician more than a moment to notice several problems. For one, the title of this song should be Blue Train. Blue Train is the name of the song and the name of the album it appeared on. That’s an unacceptable error. Also, the original recording song was performed in the key of Eb, not C, and even though the melody is minor, the solos happen over a standard “jazz blues,” which means the first chord of the solos should be notated C7, not C-. Even if you accept C minor as the key of the tune, there are all of those invented harmonies in the Real Book’s “Blue Trane” that have no correlation to chords played on the original Blue Train recording, like the phantom F-7 Bb7 notated under the pickup measure and the arbitrary A-7 D7 in measure 8. Where did they come from? Even the melody is incorrect: compare measure 8 of the original recording to measure 8 of “Blue Trane” in The Real Book. Assuming a tonality of C minor, that pickup riff should be notated G – Bb – Eb – C – Bb. Most importantly, The Real Book completely disregards the “dun — dun” response figure that defines this song, even though rhythmic figures like that are indicated for other songs (e.g. Maiden Voyage) and in some cases the arrangement of a tune is completely written out (e.g. Peaches In Regalia.)

The Sixth Edition fixes all of these problems, and dozens more, so in addition to being legal it’s a much better reference than those bootleg Real Books. But by fixing the biggest problems in the book, they made certain tunes (like Blue Train) incompatible with the earlier edition, so you can’t just bring your new book to an old book party. And even though it was thoroughly edited, the Sixth Edition doesn’t fix all the problems that were present in the original books; there are still a few head-scratchers and face-palmers in there. For an example, let’s consider the chart for Orbits, a Wayne Shorter tune written for the Miles Davis Quintet. Here is the original recording of the tune on the album Miles Smiles:

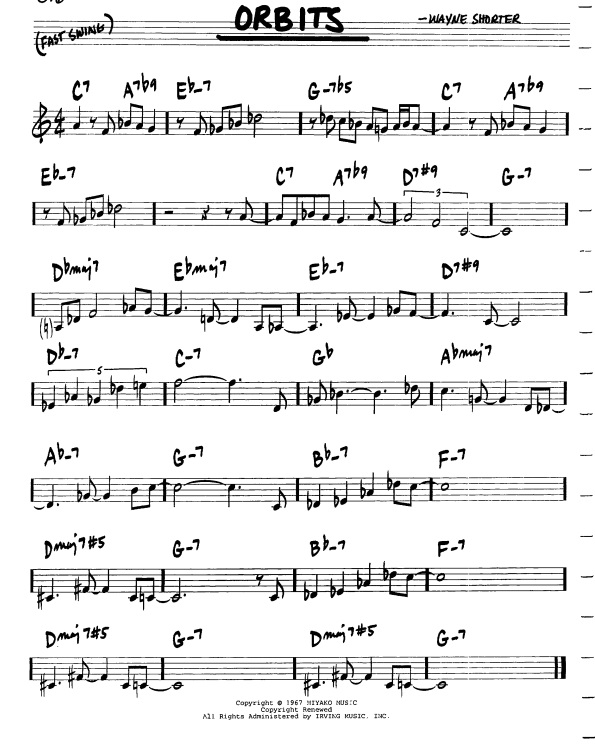

Orbits is sort of a free tune; in this original recording, any harmony is implied by the relationship of the melody and the bass. The melody itself is sort of a freeform thing, and the band doesn’t seem to lock into time until several phrases into the song. There’s no set harmonic progression, and on this original recording, Herbie Hancock doesn’t play a single chord. Wayne Shorter has recorded Orbits two other times since this original recording, and each one is very different from the others. I have never spoken to Wayne Shorter about this tune, but I would bet anything I own that this is not what he wrote:

I have to say that whoever transcribed this chart for Orbits tried hard to make it fit into bar lines. That half-note triplet? That quarter-note quintuplet? Wow! But there aren’t any chords being played during the melody on the recording, so where did The Real Book’s chords come from? Did the person transcribing just make them up? I think they did, and that should not be acceptable in an industry-standard reference work.

For example: In the recording, the bass plays C, A, Ab and G in the first phrase. So what’s with that Eb-7 in measure 2? There is a G in the bass at the same point as the Bb in the melody, so if that chord is Eb anything it’s Eb major. And the bass plays the exact same figure twice, so why are the chord changes different between measures 1-3 and 4-6? This is a mess.

Edit, September 2017: Since this was written, the session reel from this recording session has been released by Columbia Records as part of Miles Davis: Freedom Jazz Dance: The Bootleg Series Vol. 5. The Real Book lead sheet is indeed very wrong; Miles practices the melody slowly at one point which clarifies the melody of the first phrase; at another point there is discussion of a 6/4 bar and a 5/4 bar; and Herbie Hancock plays actual chords at one point after Miles tells him to “just play the chords, man.” There are enough consistencies between takes that it’s probably possible to create a usable lead sheet for this song. Hal Leonard, give me a call pls! Or you could just ask Wayne Shorter.

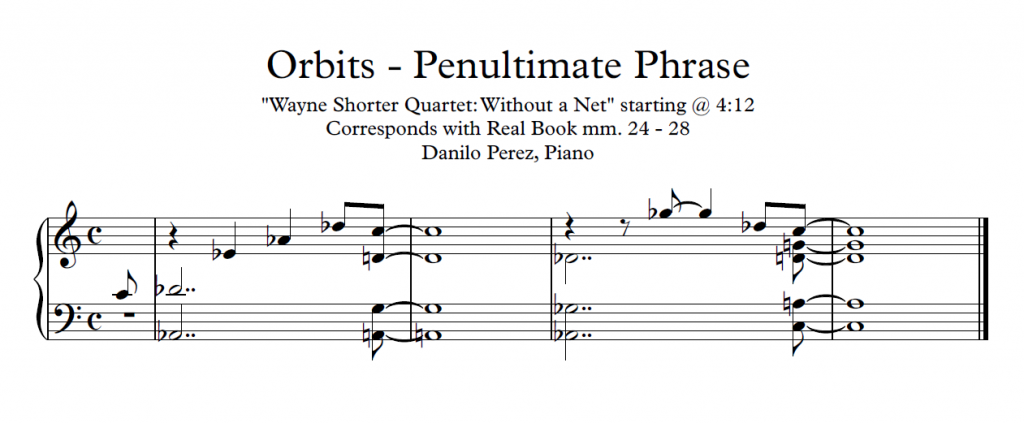

On Shorter’s most recent recording of the tune (Wayne Shorter Quartet: Without a Net,) Danilo Perez plays the second half of the head alone on piano, with chords underneath, and it seems to be mostly quartal harmony. It’s hard to tell exactly what keys he’s pressing because of all the overtones on the grand piano, but here is a general transcription of what I hear for the phrase correlating to measures 24 – 28 in The Real Book:

The chords from this transcription do not correlate to the ones in the Real Book at all. in that second measure, notated in The Real Book as F-7, the chord played on the recording is a white-key quartal harmony with an A natural in the bass voice. Whichever way you want to interpret this harmony, any chord built on an A natural is the opposite of F-7, which is what is written in the Real Book. The other chords don’t match The Real Book’s changes, either, unless you want to argue that they may be correct and Perez was playing some sophisticated rootless voicings. But I would think that since this is is transcribed from a Wayne Shorter Quartet recording, the truth is probably that either the quartal chords played by Danilo Perez were intended by the composer, or that the harmony is intended to be interpreted freely and those voicings were choices made by Mr. Perez. Chances are it’s the latter. Either way, this Sixth Edition Real Book chart is not a good reference or lead sheet for Orbits.

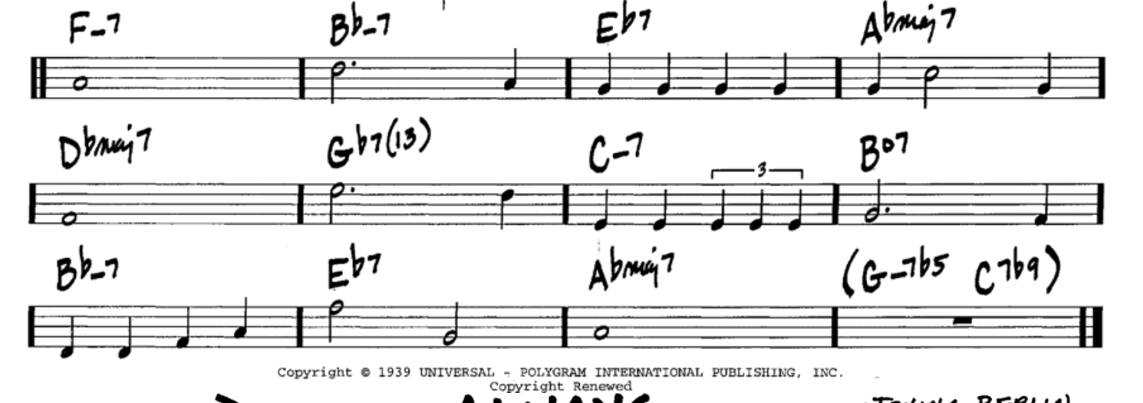

The sixth edition also does not solve the problem of including alternate chord changes without the original chord changes indicated. Here is the last section of All The Things You Are as it appears in the legal Sixth Edition Real Book:

Jerome Kern’s original chord changes are mostly intact with one glaring exception: the Gb7(13) chord. The original chord was Bbø; this is the chord in the original sheet music and also on the earliest recordings of the song. The Eb in Kern’s melody is not an added 13; it is actually a glorious, tense appoggiatura. This Gb7(13) chord in The Real Book transforms the entire nature of the passage, and is even more incompatible with the original harmony than Db-7, the other alternate chord that people learn for that measure.

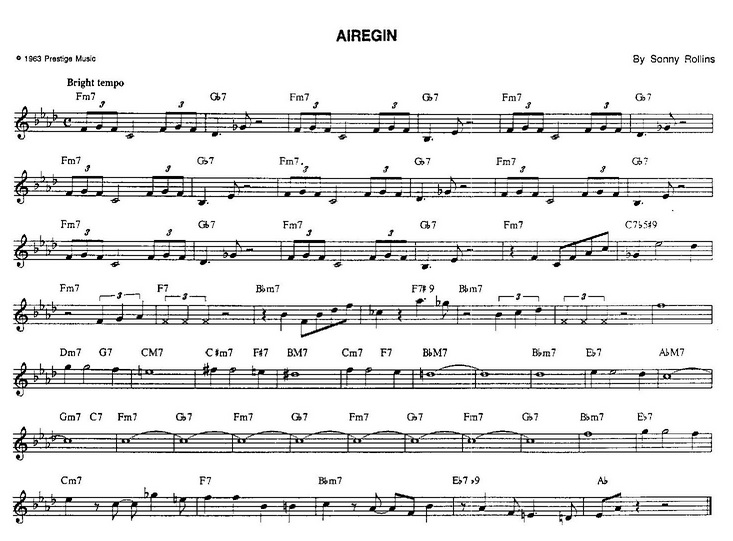

You might say I am being too harsh with my criticism of The Real Book, and you might want to remind me that most of the tunes in it are mostly accurate, and that it was much better than what else was out there when it was first compiled in the 1970s. The Real Book does get a lot of common tunes mostly right, like Cherokee and Footprints. And it sure beats a lot of other fake books from the era it came from, such as The Jazz Fakebook, which includes this practically unrecognizable transcription of Airegin:

But I don’t think I’m being too harsh. The Real Book is the most common gig book for jazz musicians, yet way too many charts in The Real Book are inaccurately transcribed or unnecessarily complicated.

This is not to knock on the kids who put The Real Book together and the folks who continued to edit it through the years. It’s very impressive when you think about what they had to work with. It’s also the book I was given when I started my improvisation studies, so I’ve definitely spent a good amount of time with it. But it’s 2014, and The Real Book is not good enough anymore.

You’re probably thinking: Okay, Mr. Smartso. You want me to ditch my Real Book? What do you recommend I replace it with? For now, like most things in life, it comes down to your individual needs. If you’re looking for a straight-out replacement for The Real Book, I highly recommend getting a copy of The New Real Book, which has been around for a while now and has several volumes. It’s widely available, is easy to use, contains lyrics, has tunes in their most common keys with common and alternate changes, and is well edited and annotated. It’s not 100% accurate if you’re into the original chord changes like I am, but it’s a book you can bring to a gig and trust. If your main use for The Real Book is to learn tunes and you don’t necessarily want to buy another book, you can visit learnjazzstandards.com and explore their resources. And if all you want is a quick chord chart to practice with or to read on a gig, there’s an app for that. The iReal app has a strong community and you can get pretty much everything you need on it, aside from melodies.

Updated September 2017: I’ve added an extra paragraph about All The Things You Are, and revisited the section about Orbits. In fact, a lot has changed since I wrote this.

24 replies on “It’s time to get rid of your Real Book.”

You spelled “Peaches En Regalia” wrong dude!

Glad to know it’s the chord chart and just not me for Blue Train though 🙂

The following is a letter I wrote to Barry Kernfeld in response to Chapter 8 of his book.

I read with great interest your book, “The Story of Fake Books,” and being identified as “B,” I’d like to make a few comments and corrections, and I can be confident that my sentiments reflect those of “C” as well. First of all, I applaud your sensitive and informed (as best as it could be) approach to what has become a world-wide phenomenon. As Pat Metheny stated, no one in their wildest imagination ever thought that the book would have the influence and recognition that it did. For all its faults, I am proud of The Real Book’s impact on jazz and the access to quality material it gave to countless musicians around the world. I’ve heard of Real Book parties, clubs that feature a Real Book Night, and school improv classes for which The RB is a prerequisite. Even the logo, which I hand-cut and silkscreened, is emblazoned on most legal imitator books.

The book was not conceived to finance our education. It was first and foremost an attempt to reinvent the concept of what a fake book was, to raise the bar for all such books to come. We both had been raised on really bad fake books that were illegible, inaccurate, useless, outdated, etc. One book I had in college contained the French National Anthem–hardly a jazz standard, you must concede. I owned about four books that were photo copies of photo copies many times over, and some tunes were barely legible. Again, our main concern was to produce something of high quality with a unique selection of tunes pertinent to the time. Knowing and having contacts to many famous jazz recording artists (Gary Burton, Pat Metheny, Paul Bley, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Steve Swallow, etc.), we had access to first-hand material that enabled us to create an important and very useful collection of tunes. Yes, we knew that we had something unique, but not one of us involved ever imagined the book’s incredible longevity. I can’t tell you how many times that I’ve been at a wedding, in a lounge, or at a private party where the musicians were playing from it.

The Real Book was featured in the New York Times and in Esquire Magazine, as stated in Wikipedia, although both articles have errors in their accounts of the book’s origins and dates. You, through your sleuthing, came the closest, which is really the summer of 1975. Having picked up the initial copies from the printer and simply walking into the Berklee lobby, all hell broke loose, and the runaway success began. It was snapped up as soon as it hit the streets, and we couldn’t sell them fast enough. A sailor from Russia bought a few copies and took them back home, and thanks to Berklee’s international student body, the book quickly spread around the world.

There were, however, only three editions produced by us. We originally intended to put out just one edition, but the last two were only validated by the number of corrections that came to us to warrant reissues. We never were concerned about staying ahead of bootleggers, of which their numbers were legion. It was never about the money–it was about the music. The extent of the care we put into the project, from going through bins and bins of albums at record stores to find composers’ names and multiple recording sources to having it proofread by a great number of qualified people, including Swallow, Metheny, Herb Pomeroy, and Wes Hensel, was a testament to our insistence on putting out the best book we possibly could. A combination of human errors and sometimes poor sources caused the mistakes the book has been so derided for. Editions #2 and #3 were an attempt to improve our original product, not to “stay ahead of the bootleggers.” We knew we could have made a pile of money had we continued, but we weren’t in the business of selling fake books — we were headed for careers as musicians — and we were definitely concerned of the legal ramifications. I do know of one particular bootlegger who snapped up our new editions as fast as they came out and then headed straight to a copy store. I hear that he continued on long after we had left Boston, and he subsequently bought a nice house on Long Island with Real Book money.

An initial attempt was made to legitimize the book, and we had meetings with two copyright experts we knew in Boston. It was determined that we would have to pay royalties of about ten cents per tune per book, which would have been about $48.00 per book–a prohibitive amount, considering that we hoped to sell it for $30.00. A large publishing company such as Hal Leonard has the clout and resources to make blanket deals with blocks of tunes, something far beyond our abilities at the time. We WERE very concerned with recompensing the composers in the early stages. After realizing that legitimate sales would be impossible, the best we could hope for was enhanced exposure to the composers’ music by which musicians might record those tunes, resulting in the Butterfly Effect of even further exposure and royalties. It seems that that has happened in spades.

I am a composer myself, and I fully appreciate copyright protection. But I do agree with Swallow that, had someone approached me 35 years ago about having my tunes in a new, upcoming fake book, I would have gladly said “Yes.” I’m very sure that the ubiquitous nature of The Real Book has ultimately been a benefit for the collective composers represented. Perhaps hundreds of thousands of musicians have learned, performed, and recorded those works that otherwise never would have.

“B”

Hi B,

I’m an independent producer working on an episode about the creation and legacy of the Real Book for a popular podcast. (I won’t mention the name here, but it has over 400 million downloads and 22 thousand 5-star ratings on Apple Podcasts.) Would you be interested in doing a recorded interview with me about your role in the creation of the original The Real Book? We’d be willing to keep your identity anonymous, if you’d like, and could even mask your voice in post-production through various means. Your perspective would be a vital part of our story, and I would love to speak with you.

If you’re interested and/or would like more information before deciding to proceed further, you can contact me at mmccavan@gmail.com.

Mikel

Hi B,

I’m an independent producer working on an episode about the creation and legacy of the Real Book for a popular podcast. (I won’t mention the name here, but it has over 400 million downloads and 22 thousand 5-star ratings on Apple Podcasts.) Would you be interested in doing a recorded interview with me about the creation of the original The Real Book? We’d be willing to keep your identity anonymous, if you’d like, and could even mask your voice in post-production through various means. Your perspective would be a vital part of our story.

If you’re interested and/or would like more information before deciding to proceed further, you can contact me at mmccavan@gmail.com

Mikel

It would have been nice if you had edited in the appropriate changes that you were talking about

Interesting article – but you’re pushing the point too hard and getting into logical non-sequiturs as a result. For example:

– “Here is the last section of All The Things You Are as it appears in the legal Sixth Edition Real Book. Jerome Kern’s original chord changes are mostly intact with one glaring exception: the Gb7(13) chord.” Yeah, but the New Real Book, which you recommend instead, has the same chord there.

– “But by fixing the biggest problems in the book, they made certain tunes incompatible with the earlier edition.” Well sure, but that can’t count as a criticism of the 6th edition specifically: anybody playing the correct changes is going to be incompatible with the error-prone earlier edition, regardless of where they got the improved changes.

I don’t think I’m pushing the point too hard, and I don’t think I’m getting into any logical non-sequiturs.

You are correct that The New Real Book also doesn’t indicate the original changes for All The Things You Are. I made clear when recommending The New Real Book that “It’s not 100% accurate if you’re into the original chord changes like I am.” But in many cases, the original chord changes are accurately indicated, either as the primary or alternate chord changes. Maybe I could have included an example where this happened, but this is not a non-sequitur.

And yes, you can absolutely criticize the Sixth Edition for not being compatible with older versions of the Real Book. This new version has some songs in different keys, and doesn’t indicate the changes they made. They designed it to look and feel just like the earlier bootleg Real Books, so there’s a lot of potential for confusion. The purpose of books like this for education, and so people can read off them at gigs, right? What if you’re on a gig or in a class where people are told to bring their Real Book and someone calls a tune like Blue Train? One person could easily end up playing the melody in C and the other in Eb. Then they’d have to stop the tune, then they’d yell at each other, and all of a sudden they can’t play at that coffeehouse anymore because they scared the patrons with their argument. It’s very easy to indicate alternate changes when you publish a book of lead sheets; Hal Leonard did not do this.

None of this is a non-sequitur.

Your article’s premise is intriguing, even if it is approximately like calling for people to stop using the internet to find quick information because that information is so likely to be misleading. You are right, but good luck.

Of course it feels silly and shallow for a player to read from a Real Book on a gig or session. But I think that if musician is serious, the Real Book (6th Edition–forget the others with so many wrong things, and it is utterly silly to think the bootleg wrong stuff should be compatible with new editions) is a useful tool–not by any means the only one needed to learn a tune. But yes the Chuck Sher books are much better and more thorough, though I think the older handwritten-look font is easier and bolder to read.

In my opinion the phenomenon of (young) players reading from “ireal” changes app on their phone or tablet is a terrible idea, far worse than using the Real Book. First of all, it misses a main element of the song–the melody–if you don’t have a melody to start with you are nowhere with it. Also any particulars about the song–rhythms in the accompaniment, harmonizations at certain spots, etc.–are all lost in a mish-mash of just kind of slogging through an approximation of “the changes”, the quotes because they are just as or more likely to be wrong than the 6th Edition Real Book, and the way they specifically relate to the melody with alterations or important guide tones is long lost. Also it adds energy to the perception that information should just be free, and that perception is a very self-destructive one for musicians.

One thing your article doesn’t really make clear about “original” harmonies: it is rare that a standard popular or theater song is commonly played with all of the original harmonies. There are conventions, and some are great improvements while some are sort of regularizing or genericizing harmonies which were originally very particular, if less colorful. I suspect in some cases the Real Book is trying to reflect the conventions by following the changes of a respected player (Dick Hyman’s two books do it more thoroughly, but that is only a couple hundred tunes). This just underlines the point that other tools are needed.

ps. the paragraphs were eliminated in what I wrote. Sorry, I guess my comment is too long for what was expected here!

As a vocalist, one problem I have with the Vocal Real Books is the omission of most intros. Intros serve to set up a tune both musically and lyrically, and often the words of the intro are critical to understand the rest of a the song.

I contacted Hal Leonard about that issue, and initially it seemed that they might do something about it, but it has fizzled out.

Yes, the verses at the top of the old standards are integral to those songs, and are very much lost. Some of those verses are gorgeous – the verse to All The Things You Are is a good example. People would be happy to learn about them.

Do you think that a book of lead sheets that included the verse would sell? That’s probably Hal Leonard’s ultimate consideration.

It’s jazz. I usuallu compare the sheet music with at least 3 popular interpretations of the song. If I was to play it on piano, by myself, I have a tendency to alter the chords to suit my own vision how the piece should sound. In a band, we sit down, analyze it and agree on how we’re going to handle the chord changes.

The real book gets footprints mostly correct, maybe. The changes cm to fm do make up the bulk of the tune but the best bit on the Wayne Shorter is the unusual turnaround and the real book gets this wrong. Chuck Sher gets it right though in his great product.

Q: What’s the best way to get someone to complain about a chart?

A: Write one.

Agree with your article! While I own all the sixth edition books, there are too many mistakes that I end up totally altering by listening to the record.

Take ‘Please send me someone to Love’ from real book 4. The original Percy Mayfield tune is in G, RB4 is in F# and the melody doesn’t capture the vocal line at all. Must have transcribed on a slightly slower turntable or something 🙂

I do think while realbooks are good at getting musicians to play together at jams, it’ll hold you back unless you start listening and analysing records yourself.

And don’t get my started on bands that all use iRealB as a crutch

The best and most accurate “fakebook” I know of is actually not a “fakebook” at all, but the real thing. I used to take music paper and a pen or some sharpened pencils with me when I went to a club to hear one or another of my favorite jazz combos play, and if they played a tune that I absolutely had to have in my lead-sheet collection I would just write it down as they played it, melody, changes, nass line if need be, to make a lead-sheet for my collection. I got very proficient at this and had myself a considerable collection of jazz standards and not-so-standards to work from. Those so-called “real books” are so full of errors I wouldn’t waste a plugged nickel on them!

It’s possible to agree with every specific criticism you’ve made – which I do – and still disagree with the general gist of your article, and with the whole universe of Real Book dissing. People putting down the Real Book are coming from a different world than many musicians.

First off, I’ve tried to be competent in many styles, like Rock, Pop, Country, Bluegrass, as well as a lot of jazz. It really helps in the studio. So, I haven’t played “How High The Moon” 1000 times. I don’t have room in my brain for innumerable standards. I know plenty, but there’s a huge bunch I don’t know. Why fumble? Fake books are pretty useful, and they’ve gotten way better over the years, spurred on by the Real Book, which, despite its many errors, was a vast improvement over what was available at the time, as you point out.

Second, there’s a bunch of great tunes in the Real Book that I’ve memorized and love to play, but nobody knows them, because they’re modern tunes. Like “I’m Your Pal”, “Virgo”, “Lament”, “Desert Air”, “Falling Grace”, “Fall”, and the list goes on. If I call one of these, I better hope the other cats have their books.

Third, standards culture often leads to sameness in set lists. Jazz has gotten so interesting from a compositional standpoint in recent years. I want to play tunes by Russell Ferrante, Vince Mendoza, Larry Goldings, Pat Metheny, and a bunch of lesser known great writers. It feels tired to be playing “Stella” all night, as good as a tune as that is. So I bring lots of charts, and the Bb’s and Eb’s for the cats.

Fourth, when someone calls a standard, there are often different changes that the players are familiar with. So, we either have to discuss this before the downbeat, or scuffle the first time through as we hear, and adjust to the other players version. And that’s assuming everybody has good ears. Otherwise, it might take a few choruses. All these problems go away if you have charts. Memorizing the American Songbook is cool, but to me, way overrated.

I don’t think you understood the general gist of the article.

I’m not ‘dissing’ books and charts, even though I shared my opinion that you should not be looking at a book at a jam session, at least not in New York City. I’m pointing out why The Real Book not adequate as a book or as a source for charts – the very reasons you’re describing.

The iReal Pro app and The New Real Book are both better than The Real Book for the types of things you’re looking for. There might even be new things that have come since I wrote this article that are better.

I appreciate your efforts to set the record straight on some of these early Real Book charts, as well as your commentary on the book as a whole. I went to Berklee in the late 70’s and owning that illegal publication was required to merely get by as a student, not to mention a player. The thing is, once you start really digging into learning the language of jazz (standards especially) via listening, transcribing, and playing, you quickly realize that, in a sense, there is no “correct” way to do any of it. It’s difficult to find two versions of a standard done the same way so… what exactly is the right way? In the case of songs based on old show tunes, you could go back to the original sheet music but it wouldn’t translate that well for the average jazz player. On the other hand, in the case of a tune written and recorded by the artist like the aforementioned “Blue Train” or anything off of say, “Kind of Blue”, it makes complete sense to use the original recordings as a definitive point of reference and should be reflected as such in an accurate lead sheet. If I had to put together a massive jazz fake book, I can’t imagine it boiling down to an exact science. A lot of it would have to be based on personal preference as well as a thoughtful assessment as to what’s most common and useful.

Interesting! Thanks for the comment.

From where I sit, there are two basic reasons why a person would want a big book of lead sheets:

1) As a book to have on hand so that everyone’s playing the same chord changes on a gig, etc.

2) As a reference / tool for learning tunes

And the original Real Book is not adequate for either of these purposes in the 21st century. I understand that it was the best thing available up until probably the 1990s, so I’m not trying to hate on it too much.

For older tunes, the most useful resources for me are the ones that include the composer’s original chords and melody… Understanding the composer’s intent is very important to me and opens up some new creative avenues on tunes where the original chords have been mostly forgotten (e.g. All The Things You Are.) But for a book to function at a gig, you also want the book to include the chords that are most common for a tune. The New Real Book is an example of a resource that checks off all of these boxes in terms of its design.

Also, I don’t understand why Hal Leonard fixed some tunes (e.g. Blue Train) but not others (e.g. Orbits)

Back in the 80s I used to do a lot of club dates/casuals. Having a Real Book was a thing, but a lot of the players, esp the older horn guys, frowned on it bc they had all learned their trade doing the ‘faking’ thing where they’d show up on a date and be told what they were expected to do – which parts in the harmony, etc. They had to know the tunes backwards and forwards, and expected all the younger guys to know them, too.

The Real Book was a saving grace back then, bc it helped teach the tunes to those of us who didn’t know them. Mine’s got as much red ink from corrections and emendations as it does black ink, I think, but it got me through.

I’ve worked with the changes there, and do some solo stuff with different reharmonizations, but I wouldn’t have learned tunes without it. And that’s kind of the point of the book – it’s a reference. The player still has to have some discretion, has to be able to transpose, has to be able to sort through some of the nonsense and play a ii-V when it’s obvious that the harmony is a ii-V and not some obscure voicing that only the chart writer thought was cool.

Dan,

Great observations!! The ever ongoing argument…Fakebooks. I remember photo copying the original Real Book from a guy who was a student teacher at my HS my Junior year back in 1980. Amazingly, someone had actually gone through and painstakingly entered the correct chords and voicings in it. I noticed this especially when playing through Dolphin Dance and whoa, those are Herbie’s voicings!!!

A few years later, when I bought a bound version from a guy who came to my college and pulled up in his van which was full of fakebooks like the Eskimo Book, The Colorado Fakebook, The Monster Book, as well as the Real Book I-II which were the only ones at that time, I opened it to look and much to my dismay it was the ‘Original’ Real book with all of its nonsensical errors. It was at that point I started to head down the path which by the time 1990 hit, I’d put my books on the shelf, stopped using them and allowed them to collect dust.

What I discovered, especially when I started lifting arrangements to play in my trio, arrangements by Oscar Peterson, Ahmad Jamal. Monty Alexander, Bud Powell, Wynton Kelly, etc was that my ears were not only developing, but my understanding of harmony and composition exploded. One of the best things during that time period was getting asked to do a transcription book of Cedar Walton (for Hal Leonard). Cedar gave me hand written charts of some of the compositions he chose, I got to choose a few songs I liked where he was a sideman. What I discovered was that Cedar reharmonizes his own things on the fly just like when playing a standard. This is the path which I’ve pursued to this day because stock changes are like doing scales, it’s not always creating music. For me, playing with a new player, or in a new group situation is about figuring how much harmonic/rhythmic vocabulary players really know. There’s so much that learning out of a book and relying on a written page doesn’t work in ‘the moment’ of creating music. I can tell within a few bars how things are going to go based on the time feel and the way the melody and harmony are being played, even before solos.

I would encourage all of you here to find a way to get away from reading out of fakebooks, start really learning melodies and the original harmonies from scores(if a musical) or transcribing different versions from multiple recordings. You’ll be surprised that if you discipline yourself and take your time, the growth process is an accelerated curve.

BTW, on the remark about Airegin from the “Worlds Greatest Jazz Fakebook”. When I saw that transcription for the first time, I recognized the it immediately. It’s not based on the way Sonny Rollins plays his own composition. This is from a Prestige recording date with Miles’ Quintet w/John Coltrane. I think the rest of the rhythm section is PC and Red Garland if I remember correctly. The Mambo-ish vamp is played as an intro, then the 1st A section starts. The ‘X’s in the melody setion are Philly Joe’s hits/fills on drumset. Instead of going back to the head melody on the repeat, they play the F minor mambo-ish vamp for the same length of time as the head 2nd time, then they play the ‘2nd ending’. The solos also use that form. So, it’s not really wrong in the Worlds Greatest Jazz Fakebook, you just have to know the recording they used.

I’ve sort of figured out as I look through Fake book indexes that with the years of listening, playing with vocalists, and even playing songs in 12 keys, I probably know a few thousand standards and jazz tunes, and even if I haven’t played a particular song in a while, it’ll come back quickly. Hal Galper and Phil Woods said in a clinic many years ago that there’s only 20 basic songforms in Standards from the Great American Songbook and in Jazz Standards. Most of the others are combinations of those 20. They are so right.

I encourage you to learn the lyrics if they exist, then you’ll know the melody, and then you get the harmony. The world is full of lazy, mediocre, players. Don’t be one of those and strive for true mastery of your art. It’s a lifelong process and you NEVER get there. Anyone who says they’ve ‘arrived’ is lying to you or is trying to sell you something. You never stop practicing and try to get better. Peace and Blessings to all on this forum and thank you Dan for taking the time. It’s so needed to be said.

Wow! What an amazing and informative thread. Thank you!

I don’t know if anyone notices this but it seems to me that very few players and transcribers have (or had) a good understanding of the diminished.

It’s probably in the notation of dozens of books and courses that I’m too cheap to buy but I wish someone early on would have whopped me upside the head and said “learn the diminished boy”

When I listen to the songs from the real book I’m hearing all these diminished substitutions that just aren’t there in the chord charts.

It’s such a beautiful and amazing way to say this is where I’m going but then not actually go there.(most of the time)

Jazz to me is all about the diminished.

It’s crazy how the early artists figured out a new way to use a chord that in ragtime for instance is used like a gimmick.

But even now if you know about how 3 basic diminished forms can accent or lead into the corresponding 1 IV V in any key and any chord variation thereof it still takes hours and hours of muscle training and ear training to be able to play something from the real book and have it sound cool. Because those chords just aren’t there. When I listen to Joe Pass I’m hearing some kind of diminished chord every other chord practically. And I’m not seeing or hearing that in the charts of any

book including the RB. So yea what your saying is actually woefully understated.

But it can give people a basic framework of chords that you can land on (or not) occasionally to imply that yes this might support the melody but I already played that once.

To most it sounds like utter chaos. If you develop an ear for jazz as a non musician your starting to hear how the diminished holds all the harmonies together like pesto in

pasta. If your a player it takes years to hear how it works and years to put that to muscle memory and authentically express yourself.

And the RB or any book is to get the melody right mostly. Those fast little phrases can be slowed down on you tube btw!

Thanks again!

Don

The ‘iReal’ app is the worst idea ever. It eliminates the most basic part of a song: the melody. No rhythm details. Just unreliable genericized chords. I see and hear young players relying on this on their phones to play tunes and it encourages only sloppiness and approximation.

Its attraction is that it costs nothing, and that is indeed its approximate worth.