A couple weeks before the Blurred Lines verdict, I wrote a short analysis of a powerpoint slide used by Gayes’ musicologists regarding the similarity between specific melodic material in Blurred Lines and Got To Give It Up. The analysis showed that not only was the melodic material in question not novel, but it is basically the same melodic material that was used by Smokey Robinson over a decade before Gaye wrote his song, and also by other composers and songwriters throughout history. I used this to conclude that there was no way you could call this a case of copyright infringement.

The response to this analysis was more positive than I thought it would be, but one criticism I received is that I focused on only one element of the Gaye family’s argument. This was not intentional; at the time of writing the article I was unaware of any other materials from the case.

The full court documents from this case were recently leaked to me, and they are very troubling. With the verdict out and the internet buzzing about its implications, it is prudent to look at these other materials presented in court, beginning with the most instantly recognizable similarity between the songs: the piano accompaniment.

Here’s the audio presented in court as Example 1: the melody to Blurred Lines placed over the piano part to Got To Give It Up pitch-matched to Blurred Lines:

This was accompanied in the courtroom by a powerpoint presentation with the following bullet points:

-

The melody to “Blurred Lines” matches with the accompaniment to “Got to Give it Up.”

-

Even where there are different chords, they resolve with no conflict.

-

The audio example matches because there are similarities in the melodies, harmonies, and phrase lengths of the two songs.

Here is example 2, the melody of Got To Give It Up placed on top of the keyboard part of Blurred Lines without pitch correction:

This was accompanied by a powerpoint slide with these bullet points:

1. Significant similarities in the melodies,harmonies, and phrase lengths result in the two works matching.

2. The accompaniment to Blurred lines is just a simplification of the “Got to Give it Up” accompaniment.

3. Based on these matches, it could be inferred that the accompaniment to “Blurred Lines” was performed while “Got to Give it Up” was playing in the background.

Because these bullet points were on a slide presented to the jury, I assume they were the basis of the Gayes’ argument regarding these clips. If I am wrong about this I will update this article accordingly.

There are several issues with these materials.

First: the audio does not match perfectly in either clip; In example 1 you can hear clashing of the melody and the harmony throughout the example even though they’ve been pitch matched, e.g. the major 3rd clashing with the minor third at :32. There is not a ton of conflict, but this should not be confused with them “matching;” they work together because they were both pitch- and tempo matched. You could make many, many melodies work with that backing track the same way so long as you matched the pitch and tempo, so many so that it would probably be harder to find a song that would not fit at least as well.

Example 2 is even less “matching”; it sounds pretty ridiculous to me to have Gaye singing a whole step higher than I am used to, and I strongly suspect that a person who has heard neither song before would hear example 2 and sense something was wrong. The fact that they don’t completely clash is a result of the tunes both being in 4/4 and having rhythm at all.

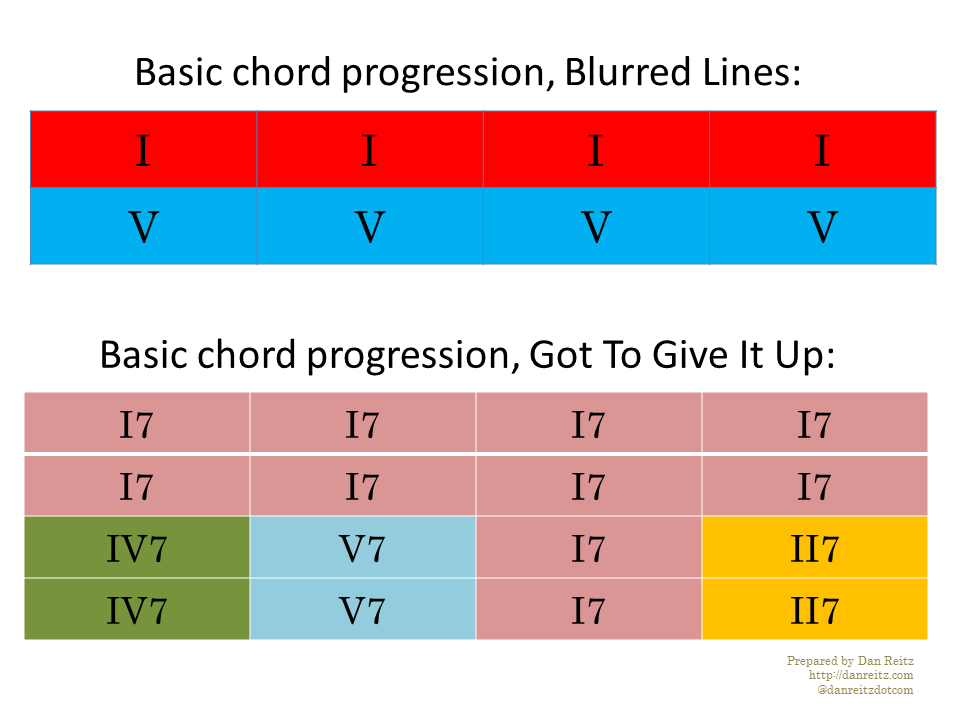

These are also different songs harmonically: Got To Give It Up uses a series of dominant 7th chords with an emphasis on the I7 chord. It also uses the II7 as a turnaround, which is very novel for a pop song, or any song, really. Blurred Lines just uses a I-V progression in its simplest form, without variation, on repeat, ad infinitum. These these two songs do share the tendency to sit on the I chord for a while rather than change chords frequently, but this is not a unique feature of the harmonies of these two tunes alone. These two songs don’t even have the same turnaround, which is probably the most novel feature of the harmony of Got To Give It Up. They are not significantly harmonically similar and I could get behind the argument that they are actually significantly harmonically dissimilar.

Got To Give It Up uses a series of dominant 7th chords with an emphasis on the I7 chord. It also uses the II7 as a turnaround, which is very novel for a pop song, or any song, really. Blurred Lines just uses a I-V progression in its simplest form, without variation, on repeat, ad infinitum. These these two songs do share the tendency to sit on the I chord for a while rather than change chords frequently, but this is not a unique feature of the harmonies of these two tunes alone. These two songs don’t even have the same turnaround, which is probably the most novel feature of the harmony of Got To Give It Up. They are not significantly harmonically similar and I could get behind the argument that they are actually significantly harmonically dissimilar.

In terms of their phrase length, which is the next point brought up by the Gaye family’s legal team, this is sort of a tricky thing to compare because of how clear and repetitive the phrases are in Blurred Lines and how loose and over-the-barline the melody is in Got To Give It Up. I would say that the length of the harmonic phrase in Blurred Lines is 8 measures, and the melody is made up of a series of shorter phrases that are around 1 and 2 bars in length. For Got To Give It Up, the harmonic phrase is a full 16 measures, while the melody is sort of a snaky thing whose shorter phrases change slightly in length from verse-to-verse. Either way, even if you heard both songs as having the same longer phrase length, there is nothing novel about 8- and 16-measure phrases. These have been the dominant phrase lengths in American popular music for as long as such a thing has existed. Pointing out the similarity between two songs for having 8- or 16-measure phrases is like pointing out the similarity between a cat and a rabbit because they both have fur.

So there are no significant similarities in the melodies, harmonies and phrase lengths that would make these two songs work together more than most other two-song pairs would work together, which means that the Gaye family’s first powerpoint presentation and the accompanying audio are all pretty much irrelevant.

I highly doubt that the Harvard musicologist who put this first presentation together actually believed that there was plagiarism going on here. Her presentation hinges on the ignorance of the jury; the bullet-points are either factually incorrect or are so broad that they could be applied to almost anything. It’s like if you were trying to prove that one novelist plagiarized another novelist and as your proof you pointed to the fact that they both published books that contained chapters, and both books had a couple of reviews on the back cover, and both books were written in English. Would these three similarities prove that one author ripped of the other? No, they would prove that both authors published a book, and it would show that books tend to contain chapters, be in a language, and have reviews on their cover. And even if there were plagiarism issues with the text of the books, it does nothing to prove this by pointing out that both books have chapters and have reviews on the covers. To do this would be cynical; you would be assuming that the jury had never read a book before.

Bringing us to the statement that is at the root of this case: “The accompaniment to Blurred lines is just a simplification of the “Got to Give it Up” accompaniment.” This was addressed in great detail in a series of slides in the second Powerpoint presentation, which appears to have been compiled by the other musicologist, the person who put together the materials I analyzed in the previous article.

Like she did with the melody, she broke the accompaniments apart and placed fragments from each song next to each other in order to draw attention to specific similarities between the two songs. Although there is no exact matching musical material, she makes it clear that there are some similar tendencies in the basslines and the right hand of the piano part:

[nggallery id=4]

This is fairly compelling stuff even though it does not contain a “smoking gun” of a copied phrase, bassline or instrumental part. The most damning similarity is the one that everyone notices immediately: that bouncing electric piano figure (described in the powerpoint as a “Rhodes Organ,” which is not the name of an instrument.) Although the chords are different (I7 vs I,) the voicings have the same number of notes and are in the same register, and they revolve around the same bop-bop-bop off beat rhythm. The similarity is so striking that most people seem to pick up on it right away, and it doesn’t help Pharell and Robin Thicke’s case that they purposefully chose to use a very similar sounding electric piano as an homage to Got To Get It Up.

But a this is hardly a novel element to a song, and Gaye was not the first to pair an off-beat piano rhythm with a I-chord dominated harmony. Here’s an example from The Skatelites that fits the same description:

Here’s an example of an even more similar groove from trombonist Don Drummond:

Both of these recordings predate the Gaye (I haven’t verified the dates on these, but both are featured in collections of recordings from the 1960s,) and these are just two of literally countless examples of Jamaican music from that era that featured the same basic off-beat rhythmic figure. It would be very surprising if Gaye were not hip to the sounds of these first-wave ska artists when he sat down to record “Got To Give It Up” since Jamaican music had become pretty well-known in the United States by 1977.

The irony is that in cutting these songs up and comparing their most similar fragments in an attempt to prove sameness, the musicologist also highlighted the clear differences between the two songs. She left the door wide open for a thorough rebuttal by the defense. Even the one element that is the most similar between the two songs is still slightly different, and can be easily proven to not have been novel. And without an outright copying of some element, which I don’t see here, I don’t understand how this could be a case of copyright infringement.

15 replies on “Blurred Lines case: An analysis of the piano arrangements as they were presented to the jury”

Good article

I’m no theory expert by any stretch.

But, to the average listener these songs do sound remarkably identical and I simply can’t believe Williams et al were not aware of this on producing the song.

Just because you change enough to make it technically different doesn’t mean it has been straight out copied but with different lyrics.

I think it’s naive to believe otherwise.

Lol Charlie, did you listen to the songs yet?

They’re both the same genre so they’re the same?

Sure, all songs in any one genre sound the same don’t they?

That’s what you seem to be saying yes…

“The similarity is so striking that most people seem to pick up on it right away, and it doesn’t help Pharell and Robin Thicke’s case that they chose to use a very similar sounding electric piano.

But a this is hardly a novel element to a song, and Gaye was not the first to pair an off-beat piano rhythm with a I-chord dominated harmony”

Does it matter if there was a previous case where they did not sue?

You said yourself the similarity is striking. The jury thought so, and they thought Thicke was a liar.

Case closed.

Did you read the rest of the article and listen to the two clips I provided that also have an off-beat piano rhythm and a similarly I-chord-dominated chord structure? Both of them predate “Got To Give It Up.”

The whole point is that as striking as the similarity is between the off-beat electric piano parts – especially on first listen – off-beat chords are a very common element in a lot of genres of music: Ska, Jamaican Dancehall music, Polka, Mexican Norteno music, etc. It’s not like Marvin Gaye invented this technique, and his heirs, their lawyer and their musicologists should know better.

I feel like you rushed through the article so that you could post in favor of your point of view. Please read the rest and listen to the clips.

Great article and assessment Dan. I saw the Gaye’s expert report which equated snippets which were never exact copying and agree with you, there’s no case for infringement here at all. Unfortunately the audio examples you posted are no longer there. It is also terrible to play two songs simultaneously, even trained ears would not be able to easily discern what is going on.

The point made in the comments at the top about the songs sounding the same is a problem for musicians. Some non-musicians think the songs sound the same, which is understandable for the untrained ear. Musicians on the other hand hear completely different melodies in these songs and correctly do not equate the songs. Influence and similar feel is not direct copying, stealing or infringement. If the untrained listener’s perception was the standard, a lot of songs would be considered direct ripoffs that are not. Stevie Wonder got it 100% correct: “I don’t think it’s a steal from Marvin Gaye,” Wonder told TMZ. “I’ve been through lawsuits for songs and all that. I think that the groove is very similar but you have to remember he is a big fan of Marvin Gaye’s so that’s okay. But the song is not like Marvin Gaye’s. It is not the same.” It was a mistake on the Blurred Lines team to not have the jury hear the recordings. In one informal online poll I saw, 52% said Blurred Lines did not remind them of “Got To Give It Up.”

Thanks, David. The audio should work now — I think it was set to “private” on soundcloud.

Dan, I was the musicologist on the other side of this case (Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke). You are completely correct in your analysis. And it has been heartening to know that the majority of people do understand that Marvin Gaye’s song was not copied. There were not two consecutive notes in the songs that were in the same place and with the same duration – rather unusual in a copyright infringement case! Keep up the good work. Sandy Wilbur

I’d be interested to know what went wrong, then. I haven’t met many musicians or musicologists that like this decision, and I strongly doubt that even the Gaye family’s team of experts believed that this was a case of plagiarism.

Let me share my analysis with you:

http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/VOLUME18/MIRROR/Pinter_2015.pdf

and a related essay here:

http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/VOLUME18/Plagiarism_or_inspiration.shtml

IMO the Gaye’s party completed a mission impossible by defending their points.

How did they do it?

The Gaye’s party avoided to get any of their points rejected, except not considering the ones that were not contained in the deposit lead sheet.

The Gaye’s party were not forced to admit that any of their points were false or irrelevant. The commonplace example songs of the Blurred party were all simply considered by the competing party irrelevant saying that only one point of similarity can’t compete with the constellation of eight similarities, no less.

The Gaye’s party criticized the point-by-point dissection of similarities even tough these microscopic details were first observed and compiled by them, no else.

They criticized the way how the Blurred party focused on the dissimilarities, while ignoring the similarities. On the other hand they did the same oppositely.

By the time of final ruling none of the musicologic points or counterpoints were mutually accepted as true or false or not significant. Even the most obvious ones. This ended up in a situation where the jury had to play the role of the expert and decide. They are not experts. They may have understood a part of the similarities, but they surely lacked the experience to judge how significant those are. Eventually the jury members were deciding by their impressions.

Seemingly this trial was a war of musicology. But IMO it was not. Real musicology played not much role in the final ruling. It turned out that seemingly any point can be convincingly counter-argued regardless of it was true or not, significant or not. It was a major defeat for the forensic musicology as a discipline.

Consider these hypothetical scenarios:

1. Artist A is making a living in music.

Artist B works in a factory, but records some songs in their spare time.

Artist A hears a song by Artist B, and believes the song has potential. Artist A makes a few minor changes to the song, and profits from the results, giving no credit to Artist B, who continues toiling in the factory.

Exactly how different, and in what ways, must the song be in order for this story to tug at your heart strings and make you feel that an injustice has occurred?

Would you feel an injustice has occurred if Artist A never heard Artist B’s work, but still wrote an extremely similar song?

—

2. Should the Bellissimo Estate be paid a royalty every time chicken wings are served?

—

3. If Gaye was alive and released “Got to Give it Up” just months before “Blurred Lines” came out, but Gaye was down on his luck, “Got to Give it Up” didn’t do so well, and Gaye desperately needed money for cancer treatment to save his life, and Pharrel and Thicke testified in court to Gaye’s face that they copied “Got to Give it Up” with the intention of making as much money as possible, would you award damages to Marvin Gaye?

Would your answer change if “Got to Give it Up” was extremely successful, but Gaye still needed more money for life saving cancer treatment?

(1) If Artist B lifts part of Artist A’s song, or samples part of Artist A’s recording, and intends to make a profit, Artist B owes royalties to the rights-holder of Artist A’s song or recording. But if Artist B twists it enough that it is no longer the same song, or makes a similar-sounding recording from scratch with different musical elements, then it is not the same song, and Artist B does not owe Artist A anything. This is why the Blurred Lines folks should not have owed royalties to Marvin Gaye’s family.

How different something has to be before it is a unique composition is a tricky question, and my understanding is that there is a lot of legal ambiguity there. I don’t think I could make a personal judgement about Artist A and B’s songs without hearing them. Even small twists are likely to be enough for Artist B to be in the clear by me, as long as there’s no recorded material or exact melodic or lyrical material from Artist A’s song or recording being used in Artist B’s song or recording.

If Artist B never heard Artist A’s work and wrote basically the same song, then it is not copyright infringement. By law, you have to prove that the infringing party was aware of the original song.

(2) No, and if you look into it, the Bellissimo family probably didn’t invent the Buffalo-style chicken wing. Their claim that the Anchor Bar was the first place to serve chicken wings doesn’t appear anywhere until well after after chicken wings became popular, and their story has changed over time. There is another place in Buffalo that no longer exists that also laid claim as the first place to serve Buffalo-style chicken wings, and lost in many accounts is the fact that wings were a staple food of poor folks in the South for a long time. There’s even a theory that the first wings served at the Anchor Bar were prepared by a cook there, not by one of the owners.

This being said, recipes are not subject to copyright. Trademarks are, but the Anchor Bar does not own the trademark to the term “Chicken Wings” or “Buffalo wings.” So no.

(3) Got to Give It Up is a different song than Blurred Lines. There would be no justice in awarding royalties to someone on false grounds, no matter the reason or the circumstances.

“By law, you have to prove that the infringing party was aware of the original song.” TIL

Thanks for indulging me 😛 My head was spinning trying to digest everything and I thought asking questions might help me let go of legal precedents and think about how things ought to be, instead of how they are.

IMHO not only is Blurred Lines sufficiently different than Got to Give it Up that infringement did not occur, but in addition, I think Gaye’s copywrites should have died with him, if not long before, and I’m not sure how strong I think copyright SHOULD be.

I would like artists to be able to make a living from their craft, however, music has a great tradition of evolution and referencing that also needs to be honored by our laws.

IMHO Sam Smith sufficiently re-framed Tom Petty’s melody that Smith’s use is fair. At least, I feel it is morally OK, even though it is not legal.

It’s the jury’s job to nullify unjust laws.

[…] and to me directly. My analysis showed that the plaintiffs, who won, presented materials that were misleading, self-contradictory, and in at least one instance, glaringly inaccurate. I concluded that the plaintiffs and their high-powered musicologists were likely playing upon the […]