If you are a frequent Spotify user, you’ve probably heard the ad that says “Piracy is so last year. Every time you listen to music on Spotify, you make money for the rightsholders and artists.” If you haven’t, you will; it is aired about once every two hours.

I am a frequent Spotify user, and I think it’s a fantastic service, offering free access to an ocean of recorded music, including recordings that are hard to find in record stores. It has revolutionized the way that people consume music and will likely be around for a long time.

But Spotify is a young product and a young company, and Spotify’s claim that it generates revenue for artists deserves thorough scrutiny. Does listening to music on Spotify really help support your favorite artists? Is Spotify really a better distribution channel than the best illegal filesharing services?

The short answer to both of these questions: Sort of, but only barely, at least right now.

Until Spotify came around, the best digital music distribution service had been Napster, the short-lived filesharing service that let users share their entire digital music library – for free – with everyone who was logged in at the same time. This provided users with a virtually limitless music library. It was wild. At one point, I had 22 days worth of music downloaded to my college computer, including rare Beach Boys outtakes, out-of-print jazz records, and new music that was not available at the mainstream record stores. But Napster did not generate any revenue for rightsholders on its own, and was successfully sued by the Recording Industry Association of America and shut down in 2001.

Napster’s longest-lasting impact on the music business is that it showed that online distribution of digital music was the future of the industry. Several online services came about in Napster’s wake, but it wasn’t until Apple introduced the iTunes Store that consumers had a stable, safe, industry-sanctioned online music distribution service that rivalled Napster in its ease of use and breadth of content. Like Napster, iTunes Store users had hundreds of thousands of individual tracks they could search for and download. But unlike Napster, a user had to pay about a buck for each download. The success of iTunes’ pay-per download model created a swamp of copycat services including Rhapsody, eMusic, and a pay-service run by Roxio that was given the Napster brand after Roxio aquired it in bankruptcy liquidation.

Spotify operates as a bridge between the two models. Users can have free, ad-supported access to stream the entire Spotify catalogue, or they can pay about $10 a month to be able to download an unlimited number tracks from Spotify to their computer. Tracks downloaded through Spotify can’t leave the Spotify application, so there’s no risk of them being distributed any further, and rightsholders are paid a nominal rate every time someone plays one of their tracks using the Spotify service. This rate is exponentially less than what would be received for one iTunes download of the same track, but Spotify still has the full support of the Recording Industry Association of America, meaning it’s legal and it’s probably here to stay.

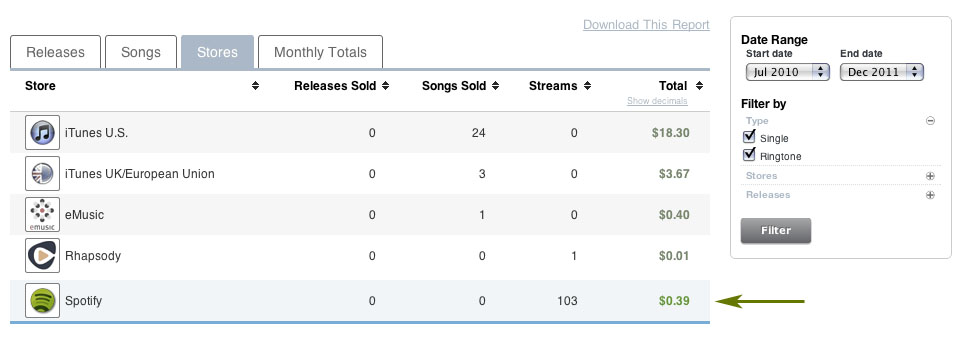

To give you an idea of Spotify’s payout versus iTunes and similar services, here’s the first revenue report for Don’t Punch Your Friend in the Head, a song my band Ramforinkus added to several internet music services last April.

The report above shows the different revenue that 28 sales and 104 streams generated across five different services. Not a great start, for sure, but not too bad considering we hadn’t really promoted the song yet. Since the band doesn’t have a record label or any other stakeholder taking a cut of the revenue, we receive the entire payout from each service:

iTunes (UK/EU) ~$1.22 / sale

iTunes (US) ~$.76 / sale

eMusic $.40 / sale

Rhapsody $.01 / stream

Spotify $.00378 / stream

So if you live in the US and purchased a copy of Friend in the Head on iTunes for 99 cents, we would receive about 77% of the sale. This could add up pretty quickly; if we end up selling 9,900 copies of our song on iTunes, we’ll receive about $7600. That would finance a short tour for sure.

Spotify has a completely different business model than iTunes in that it is a streaming music service, not an online store. As such, it pays rightsholders based on individual plays, not downloads, and its current rate is a little less than four-tenths of one cent per stream. That means an individual user would have to stream our song two hundred times in order for my band to receive the same 76-cent payout that would come from a single purchase on iTunes. This won’t add up in any meaningful way until our song receives hundreds of thousands of streams, and my guess is it is unlikely that someone would listen to any individual track by any independent artist on Spotify enough times to match the revenue of a single iTunes purchase.

For the record: Four-tenths of a cent per stream is a marked improvement over the way artists were initially compensated by Spotify; Lady Gaga famously received only $167 after her song “Poker Face” was the first track to hit 1 million streams on Spotify in 2009, which amounted to 1.67 thousandths of a cent per stream.

This figure – .38 cents per stream – shocks a lot of people at first because Spotify’s entire business model rests on the fact that it’s supposed to generate revenue for rightsholders, and they vigorously refute the idea that they are anything other than the next great revenue source for artists. In a recent interview, a Spotify spokesperson said “Spotify is now generating serious revenues for rights holders; since our launch just three years ago, we have paid over $100 million to labels and publishers, who, in turn, pass this on to the artists, composers and authors they represent. Indeed, a top Swedish music executive was recently quoted as saying that Spotify is currently the biggest single revenue source for the music industry in Scandinavia.”

That claim is certainly impressive, but there’s a serious disconnect here between what Spotify says and what artists end up receiving per-play on the service. Most major labels keep a considerable cut of that less-than-four-tenths-a-cent payout, and independent artists who release their own material generally don’t attract the number of listeners it would take to make Spotify a better revenue generator than iTunes.

In fact, I might argue that fans who pirated Don’t Punch Your Friend in the Head could do more for us than had they used Spotify to listen to it. If 103 people had pirated Friend in the Head instead of streaming it through Spotify, those 103 people would possess a digital copy of the song, which means there are dozens of extra ways they could pass it along to others. They could burn it to a mix CD; They could listen to it using any audio player, in any setting, and could easily transfer it between devices; They could convert it to any format, they could add it to a video, they could sample it, they could make it their ringtone, they could play it as house music at a theater or club, and they could broadcast it on their radio show. By listening to Friend in the Head in Spotify instead of pirating it, those 103 people could have shared the tune with other Spotify users and could have added it to their Spotify playlists, but there’s not much else they could have done that would help the song reach new people since music on Spotify can’t leave the Spotify application, and you can’t take the Spotify application with you without paying $10 a month for it. So as an artist in several independent bands, I don’t see how Spotify is really better for us than an equally accessible piracy channel would be.

I don’t mean to complain about Spotify as a service. Spotify represents the future of music consumption. We are a culture of convenience, and nothing is more convenient than immediate, cost-free access to every song you’ve ever wanted to hear. And I was always okay with small-scale music piracy, whether it meant taping songs off the radio, ripping a library CD to your computer, or making mix CDs for friends, so I am not writing this article to complain about music consumers who do not pay for all of the music they listen to. I am not only happy that Spotify is an option for my own music but I also use it several hours a day, both for fun and for work. The problem, as I see it, is that Spotify boasts that they have surpassed piracy and that you, the Spotify user, are supporting artists by using their service. I find this hard to swallow because they’ve released no data or projections to support these claims and their defense of their payout model is always presented in general terms. Spotify should not be advertising that their listeners generate revenue for artists; this could lead to someone choosing to listen to a song on Spotify instead of purchasing it on iTunes with the idea that they were supporting the artist either way. In reality, it takes nearly 300 Spotify streams for one member of an independent band to be able to buy a cup of coffee at a bodega, and probably many many more times if an artist has a record label.

If Spotify wants to change my mind, they’ll need to publicly release their payout model, and I’ll need to see concrete, verifiable data that can confirm that Spotify users listen to individual songs at a rate that will eventually surpass iTunes revenue. Until that happens, I will continue to look at Spotify as a free music service, like Napster and Grooveshark before it, and it should be known that the best way to support your favorite artists is to purchase their music at full-price – especially their self-released material – and to go to their shows when they’re in town.

Update (12/2012): In response to a few comments, I’ve expanded this article and have clarified some of the language.

31 replies on “Spotify? Not much better than piracy.”

Great article. I’m writing a similar one myself, with perhaps a different slant. Hopefully more and more musicians (independent or otherwise) start realizing this and either yank their music from Spotify, or continue to try to educate fans of music why it is important to pay/give back to artists they love.

Thanks brother.

The option is still there for fans to purchase cds or mp3s alongside Spotify. Just in the same way that book libraries operate whereby you never own the product but loan it. Books are now as popular as ever even though we have the option of renting them or going digital.

The subscription I am paying each month in the UK is $15 or so dollars more than I would be paying otherwise and the artists get the actual exposure they deserve. If you have to purchase everything to hear an artists work, how many great albums are you going to miss in your lifetime?

I agree completely, Paul. Spotify is a great way to hear new music and probably the best way for an artist to get their music heard across the globe.

The point I tried to make with this article is Spotify advertises that their service directly supports the artists, but the artists you listen are receiving almost nothing of the $15 a month that you’re paying to Spotify, at least on a per-stream basis. In this sense, it’s not much better than piracy.

I mean, piracy gives bands exposure, too. Using the original Napster, I was able to download about 24 days worth of music that I would never have heard about otherwise. This music was downloaded to my computer, so I was able to burn my favorite songs to CDs and pass them around to friends. This network of mix CDs and filesharing opened up a whole world to me that would have otherwise been closed. This lead me to go to shows and purchase music that I never would have purchased before.

I see Spotify as just the latest development in the world of free music: artists get great exposure at the expense of not getting paid for their music being spread around. The only difference this time is that it’s legal. I don’t mind this. I just don’t think they should be advertising that they support artists, unless they change their business model.

Napster and Spotify are generations apart. How can you compare exposure?! Spotify is integrated with social media and has the ability to share music. Also, people can see what you’re listening to. That is a massive difference to piracy and Napster et al. Most pirates download indulgently for themselves, Napster never had sharing functions; your friends didn’t know what you were downloading/listening to. Spotify has made it very accessible and very easy to share music with friends. And that provides a lot more exposure than the dent that pirating gives.

I’m also pretty sure that Spotify had to buy the rights to these songs; so if it wasn’t okay with artists/bands/labels then it wouldn’t really be happening. I think there’s more to it than those sale figures you’ve managed to scrape together. Since when have labels give away free music? NEVER. Somewhere down the line they are making something. It’s like the whole YouTube saga. They all got paid.

I wouldn’t ever worry about the artists signed to labels; they will always make a deal and get paid. It’s the independent artists that suffer and it’s not down to Spotify. It’s down to the big labels. Spotify started off as a free to use service, unlimited streaming as many times you want. Since the labels have been pressuring them it’s changed. This is what will impact the independent artists. 5 listens to one song? Capped hours of listening? How does that help the independent artist? How many people will use their Spotify hours to find new music and share new music? How many will want to stick with what they know?

I don’t know if we’re talking about the same Napster, bud. Napster, in its original incarnation, back in the year 1999, was incredibly social for its time. You could browse any user’s library, chat with people, etc. You had significant control over how your music library appeared to others, and definitely could tell what others were listening to and digging on. I particularly don’t get what you mean by “Napster never had sharing functions,” considering sharing was its primary function (!!) and things like Facebook didn’t exist.

Napster was as revolutionary as it was short-lived, and I see Spotify as the next logical step in the world of social, cost-free access to music. It is clearly superior for most users to Napster, just like today’s average Olympic swimmer could smoke the world record holder from 40 years ago. But just because something is great (like Spotify is) doesn’t mean that it should be allowed to make dubious claims. Their claim that using Spotify generates revenue for rightsholders is not false outright, but is misleading at best. You’re right about exposure. Exposure is great. Discovering music is great. Spotify is about as good as it gets in these areas. But I don’t see Spotify as being enough an improvement in the revenue department for them to make claims that they are better than piracy. Just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s better.

I also don’t quite understand what you’re getting at with your third paragraph. Please explain it to me.

I whole heartedly agree with this article.

Although Spotify does generate more exposure for bands, artists etc. both independants and those signed, it is not giving a fair pay out in return…

It’s as good as piracy, as they are robbing the contributing artists blind!!

I have never heard of such a poor payout in royalties, ever, and one can only hope that it improves as time goes on, and as you said, they develop the busines model further.

Peace

I agree with your points and I understand how hard it can be to accept change but Spotify is here to stay. I could also write a whole with this point but I will keep it brief.

One major plus for artists on Spotify is, unlike purchasing a song for .99 cent, Spotify pays the artist each time this song is played… forever! This means, overtime, if the songs/albums good the artist should actually make much more.

With all due respect – based on the stats in your article, your bands not necessarily lighting the charts on fire. It doesn’t seem like itunes is paying you much either. Sure, you made more money on itunes short term but if you leave your song up in Spotify, post another screenshot of your stats in 2 – 3 years and I bet you will have made twice as much off spotify vs iTunes- that is if your music is worth listening to.

To say Spotify is nearly the same as stealing is just wrong. See, after the buzz of blogs, friends, family have bought your album, it will get lost in the abyss of itunes – never to be seen again. Piled under tons of other music but tons of better and worst artist. Spotify not only allows your music to be heard and paid for as long as your music is on the service, but it also allows people to actually find your music easier.

In the long run, artists, labels and fans all benefit much more with Spotify than a record, a tape, a cd and a sold MP3. Gone are the days of Albums and here are the days of Songs… consumers aren’t spending 10 – 20 on albums unless your the Beatles or Radiohead. Spotify’s business model is not good for capitalizing on a Fad or a Trend band… but if the music is timeless, Spotify is a bands/ artist/ label’s best friend.

I hear you Edgar, but I think you’re missing my point. I wrote this blog post because people whose goal is to actively support musicians need to know the details behind Spotify’s business model. By advertising that listening to music on Spotify supports the artists, Spotify is leading people who would want to actively support musicians to think “Oh, I’ll just listen to this new song on Spotify instead of buying it, and that will be just as good.” It’s not as good, unless you’re going to listen to the song two hundred times, you dig? And I didn’t say Spotify is the same as stealing, I just said it’s no better for artists than piracy, because a music consumer can do much more with a digital copy of a song that he pirated than he can through the stream-based Spotify application.

And I need to stress that I totally love Spotify as an application. It’s fabulous. I’ve discovered so, so much music through it, and paying the $10 so I can take it in the car with me is one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. It’s the future of music for sure and I don’t doubt that over time, artists will see good returns from it. But it’s not a direct way to support the artists, which is something that is sort of implied in their advertising. Buying music on a service like iTunes or paying admission to a concert are much more direct and will get more money to the musicians – if that’s what a listener cares about.

I agree paying is cool too, but your facts are just kind of wrong but well intended. I hope I am not being rude – just wanted to share the truth. This link does a good job explaining – http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20120622/16193319442/myth-dispensing-whole-spotify-barely-pays-artists-story-is-bunk.shtml

Edgar, I don’t understand how my “facts” can be “kind of wrong,” since the main “fact” I cite in this blog post – that Spotify pays artists a little less than .4 cents a stream – was the result of simple addition and division. If you can refute that figure in a way that is verifiable or is cited across several sources, then we can talk about my “facts.” I think the term you were looking for is “your analysis is flawed.”

Thank you for offering that article for consideration. I read it twice, and also read two of the articles it cites, and read about thirty of the comments. It is uninformative and noticeably biased, but it provides some broader context that I did not consider when writing my blog post. I think it would be a disservice to this conversation not to address it at a point-by-point level.

I’d like to begin by looking at the author’s primary claim. He writes “A few months ago, someone at one of the music collection societies told me about an analysis they had done concerning the amount of money paid per listen” through Spotify vs. radio, iTunes and – quote – “lots of other things.” Without giving citing any figures, nor identifying nor quoting his source, the author makes the bold claim that “Spotify pays a hell of a lot more than any of those other sources. It’s just that it’s incremental so it looks smaller.” While it’s absolutely true that Spotify pays artists more per-stream-per-listener than radio does (exponentially so,) the Spotify vs. iTunes payout comparison is not so cut-and-dry and the author gives no numbers and minimal context to support his claims. I’m left underinformed and skeptical of his motivations. Who was his source? What specific data was analyzed? Who did the analysis? How was the analysis performed? What were the results, and how do they support the claim? These are the things I need to know before I give creedence what he is saying. Here’s an analogy: My Uncle owns a mini golf course that claims to have the longest hole in the world. Someone has yet to claim that theirs is longer, but if they did, I couldn’t end the dispute by saying “my friend from the Mini Golf association measured both mini golf holes, and he assures me ours is longer.” I’d have to at the very least identify my source and give the measurements he came up with. Better would be for me to explain how he arrived at that conclusion and let the other side take their own measurements for verification. Likewise, I will not be convinced that Spotify is truly better than iTunes in terms of artist revenue until I see the relevant data about iTunes and Spotify use. It would look something like this: “Spotify users listen to individual tracks an average of X times per month. The average highest number of streams of one song per user per month is Y. It is projected that over the course of 10 years, a user will listen to her top N songs an average of Z times each.” If we knew that the average user will listen to her top 100 songs an average of 1000 times each, for example, then we could have a solid conversation of which service is better in terms of artist revenue and why.

The most concrete claim in the article comes from Merlin, which claims “Spotify’s payouts to Merlin’s 10,000-plus indie labels rose 250 percent from the year ending March 2011 to the year ending March 2012” and that the low payouts that make the news were “payments from quite some time ago, not what’s actually happening today.” It is important to note that the improved year – April 2011 through March 2012 – is the same year I based my analysis on. So the .4 cents per stream figure that I arrived at through high-tech addition and division is the improved figure, reflecting the 250% growth. (Based on the 250% figure, Spotify’s 2011 payout would have been closer to .16 cents.) The .4 cents a spin figure has been pretty widely quoted over the past year, so it’s not exactly true that the figures that are floating around are “payments from quite some time ago,” but he’s probably referring to the Lady Gaga figure that I mention in my blog post, which is the type of story that has a lot of staying power. If this is the case, he should have referenced it outright to blast it from our brains.

I completely agree with Merlin’s other claim: that the record labels are to blame if their signed talent receives less than .4 cents per Spotify spin. Spotify has been unambiguous that it pays the rightsholders, not the artists, so it’s not really their fault if a signed artist receives only a fraction of the fraction of a cent their label received. It still doesn’t change the fact that most signed artists see very little revenue from your activity on the service. If more people knew that the rightsholders were generally the record labels, do you think they’d be as enthusiastic about Spotify in terms of it being better than piracy?

The rest of the claims in the article come from a guy associated with Spotify itself, so it’s in his interest to make Spotify look as good as possible. His first claim – that 70% of Spotify’s revenue goes to copyright holders – is great. We don’t know how much revenue they generate, of course, so I’d stop short of sounding the trumpet quite yet. His second claim – that Spotify users “spend” twice as much “into the creative community” as compared to iTunes – is unsubstantiated and raises a slew of questions. How did he arrive at that figure? How does he define “the creative community?” Artists? Labels? For that matter, how does he define the words “spend” and “into?” And what would Apple say if it was pressed for a response? Might Apple do their own study and come to the conclusion that iTunes users in fact “spend more into the creative community” than Spotify users? It’s possible. His third and final claim – that Spotify’s per-stream payout is increasing as the service itself increases – is very easy to understand and is a very good explanation of what’s going on. To paraphrase: “Things are a little weird, but they’re not as weird as they used to be, and they’re getting better.” I appreciate this, and it gives me hope that my concerns will soon be irrelevant. But again, this guy is involved with Spotify, so it’s in his interest to make Spotify look as good as possible.

At the end of the day, this would be a much easier conversation if Spotify’s business model was more transparent. But it’s been a proprietary secret since day one. So while people debate the merits and evils of Spotify, the truth is hidden, silently mocking us.

Before I sign off, I cannot stress enough how much I like Spotify. It’s the greatest. It’s better than the current piracy models – The Pirate Bay, Gnutella, Rapidshare, etc. – for me, personally, as a music consumer, since it provides access to the widest amount of music in the easiest way. I could write a dozen blog posts about how great Spotify has been for me as a musician and a music listener. My issue involves the ambiguity of its business model, and the way it misleads or underinforms consumers regarding the revenue it generates. On that level, I’m not sure it’s better than piracy – in general – for artists, meaning if there was an “illegal” service that had as much music content as Spotify but also provided the user with the benefit of possessing a digital copy of the song, I don’t think you could say that Spotify was better than that service.

In the end, I appreciate that it’s trying to correct its image, but until Spotify gives us specific numbers and substantiated facts about its business model, it is making things worse for itself image-wise by appearing evasive.

I’ve been known to on many occasions buy the music I want, but not import it into Spotify and listen to Spotify’s version to give the artist that little bit more. Spotify may not be the best system, but I have found ways to give more to the artists I want to support than in the past. I also know I am probably not the norm, but many that care don’t know it can be exploited in this way.

I stopped buying music online entirely. Seeing as the legal paper says I am pretty much “borrowing” anyway and my purchase does not stand up in court. I use Spotify premium and if I like something greatly I buy the CD or go to the show and buy the CD to support the road. Until I can get FLAC or WAV or AIFF for same cost as a CD this is my model. I am already bummed at my 128kbps-256Kbps purchases that sound terrible and need to be re-bought at better quality anyway. Spotify at 320kbps and CD rips at lossless and I am happy.

Well, if you want more than that from Spotify, I guess you’ll need to raise the price for using Spotify Premium (or advertising at the free version) several hundred times. I mean, I might listen to like 300 songs on Spotify every day (haven’t counted, but a rough estimate), should I pay like even 50 Swedish öre for every song, I would be ruined in a month. Now I pay 99:-/month, and have practically stopped loading music from The Pirate Bay and so forth.

You might discuss the percentage that Spotify keeps though, but that’s probably no answer either, to “high volume users” like me. And yes, I used to steal physical CD’s in stores until like 2003, so I have nothing against stealing, and that goes for anything.

I have to admit to not having finished reading the article so I shouldn’t really be commenting yet, but here’s a question:

Are the users streaming your song likely to have bought the iTunes version if they couldn’t stream it? Perhaps some of the Spotify streamers aren’t replacing iTunes buyers; perhaps they are in addition to the iTunes buyers.

This is a common misconception I think the movie industry has – that they are losing out on revenue to pirates who otherwise would have paid to see the movie in the cinema or bought it on DVD. While this may be true to an extent, I’m sure a large chunk of the pirates would still not pay full cinema/DVD price to see the movie even if they couldn’t pirate it. I propose that these types of consumers would probably consider streaming at a manageable monthly fee as the only alternative to piracy.

It is hard to know which of the streamers would have paid for the higher-priced, non-streaming alternatives, and how many are simply additional revenue for you. But bear it in mind – some of these Spotify users may be generating money for you that you would not have otherwise had.

Judging by my own music consumption, most of the people who listen to our recording on Spotify would likely not have purchased it on iTunes, so they are almost definitely an audience separate from the audience that would buy our track on iTunes. But don’t confuse an expanded audience with increased revenue. I’d stop short of saying that Spotify users are generating comparable money for artists because the money generated is around a penny for every three streams – and that’s before any cut taken by a label or other stakeholder. Maybe I’ll be proven wrong in the end, but my guess is that Spotify will not be a major revenue source for artists unless it continues to improve its model.

Stumbled on this from Google while trying to find a way to sort Spotify playlists by year of release, an option I think they should add. (It apparently doesn’t exist.)

Personally, I think receiving 1/200th of the royalties on every play is a far better deal, at least if you’re making good music. (And if your music isn’t good, then I really don’t care if you’re failing to get rich off it.)

If your track’s good, I’m likely to listen to it a heck of a lot more than 200 times in the lifetime I’m using Spotify, which if the service remains available to me will likely be many years to decades. For the MP3, sure, you get a bit more up front, but you get that precisely once, assuming I make backups so I don’t lose it.

It would be flat-out wrong to expect even remotely similar remuneration for a single play compared to what you get for unlimited plays through an iTunes US download.

And as others have pointed out, you’re also completely missing the point that I may already own your song, but I may be streaming it to save me finding it. Or I may stream it two or three times, and then buy it on CD or MP3. The two aren’t mutually exclusive.

Proclaiming that “hurr durr Spotify users are pirates durr” is frankly ridiculous. If you don’t like the service, don’t put your song on it, and don’t sign up with any label that requires you to do so. It’s that simple.

What article did you read before you posted this comment? I didn’t say Spotify users are pirates. I said the service isn’t clearly better than piracy for most musicians. There’s a big difference between these two statements. I gave a lot of reasons why I think so, and I’ve also already addressed the issue of streaming vs. purchasing over time in the comments. No one in their right mind would expect Spotify to pay the same amount per-play as iTunes, and that’s not what I’m arguing.

My motivation in writing this article is that Spotify – a business that does not divulge its business model, and which at one point was paying at rates of thousandths-of-a-cent per stream – has been claiming that it is the fix to piracy, that it is better than piracy, and that using their service supports artists and rightsholders. My primary argument is that it not necessarily better for artists than piracy, at least not yet. Again, I gave a lot of reasons in my article. I’m also not arguing that people take their music off Spotify. I certainly plan on keeping my music on there. Again, what article did you read?

As I’ve said at least once before, if Spotify wants my full endorsement, they need to generate and release basic data about how people use the service. If you told me that over two years, the average person listened to their top X songs an average of Y times each, or that the average track generated Z dollars for its rightsholders over the course of M months, then we could really have a conversation. Until that happens, this issue will be a murky one, and I stand by my article.

I’d welcome another response from you, but read the article again before you reply!

Let me see if I understand correctly.

You have a platform to expose your music to the masses.

-AND-

You get paid for it?

Newsflash: Most businesses have to -PAY- for advertising. They don’t see it as a source of revenue.

The funamental problem is you want to get paid for recorded music like people did last century. Sorry, but that business model is gone.

Innovate or die.

I am not expecting any digital recording of any of my bands or projects to generate a ton of revenue, at least not right now. In my article I even condoned piracy, since it’s ultimately a great way to get music spread around. My concern is really with the music fan who might choose to listen to an album a few times on Spotify rather than purchasing it iTunes under the pretense of supporting those who produced the recording. They need to know that their purchase on iTunes (or an in-person purchase) will likely be of more support to the artists, unless they really do end up listening to the album hundreds of times.

That being said, recorded music is much more a product than an advertisement. Calling recorded music an advertisement is like calling any recorded intellectual property an advertisement. Does a book become an advertisement when it is released as an audiobook?

Do you make music? What would you consider an innovative way to generate revenue from digital content?

I think that because your music was streaming on Spotify, people liked what they heard and bought it on itunes, or Amazon.

If your music wasn’t on Spotify, I think the sales on itunes would be remarkably lower. Spotify pays its royalties to stream, and consumers get to hear full songs and then decide if they want to buy the songs. It’s like radio air play, except the people get to hear what they want. The rights holder of the song decides if they want their stuff on Spotify.

I’m not sure this is anywhere close to a reason to “yank” music from Spotify. Since you’re in a band, surely you understand that artists get such a bigger payout from shows they put on vs the music they sell otherwise. I’d rather get exposed to 103 people and have half of them buy $20 tickets to a show for a total of (low-balling it) $1020 than force them to buy a track on iTunes for $1 and have half of them buy a ticket. Now you’re looking at $258.30.

Would your band like to make $1020.38 or $258.30? Thought so.

I vote to not “yank” your music off Spotify.

I found your article quite interesting, but after reading it, I was left wondering what type of royalty does the artist get when a Spotify user selects their song as “available offline”?

I’m not really sure how that works… I don’t believe it downloads the track to your device, but keeps it in your cache. If that’s the case, then Spotify isn’t paying the artist for an accurate time of streams, considering that playing the song offline isn’t technically streaming. On the other hand, it might be considered a sort of download and thus pay a higher royalty if your song is made available offline. Or is it that Spotify pays by times played vs. times streamed? Do you have any information on that?

This is interesting. But, whereas iTunes pays on a per-sale basis, Spotify pays on a per-stream basis. Most people who buy on iTunes only buy once, but if you use Spotify, you pay the artist per stream. If you listen 200 times, then forever after, you are making the artist MORE money than if you have bought it on iTunes. I see this as an incentive to make better songs that people will listen to. I can certainly say that I have listened to some songs about 200 times, and these are songs that I wouldn’t have bought on iTunes. So, to make your artists money, crank up the Spotify. You don’t benefit artists by criticizing their smallest source of revenue.

I feel like you’re ignoring the fact that a lot of Spotify users will go and buy the track after streaming it for free. Spotify lets people listen to music to figure out what they like, but then to assume that nobody ever buys any tracks is a little ridiculous. I think of it more like the radio where you’re probably helping your sales by getting exposure on Spotify.

And songs I actually purchase I listen to over and over. I put them in playlist on my phone and iPod and listen to them while running so even if you were comparing streams to sales you should realize that each sale could be equivalent to many, many, plays.

Someone who listens to a song once was probably never going to buy it because they just weren’t that into it. It’s extremely misleading to compare a stream to sales. I’ve streamed “Gangnam Style” probably 80 times on Youtube by now. And people around the world streamed it over a BILLION times. Does that mean that nobody ever bought the mp3? Does it mean that I didn’t buy the mp3? (Hint: I paid for the mp3 like millions of other people who sent it to the top of the sales charts).

More streams=more sales, so I find these direct $ comparisons plain silly. I’ve bought a ton of stuff I heard on Spotify so the artists actually got paid more than if I had just bought it. Maybe only 2 cents more but why are you complaining? Show me the evidence that it’s LOWERING sales via other outlets and you’ll be a lot more believable, otherwise it’s as ridiculous as claiming that the radio playing your song is causing your album sales to suck. Songs being on spotify boosts the likelihood that I’ll buy them. This doesn’t mean that I’ll buy every song I ever listen to on Spotify-if you look at the most popular songs on Spotify they largely mimic popular radio tracks anyway so people clearly use it as a radio.

I’m not ignoring anything. I don’t think very many people will buy the music they hear first on Spotify. Has anyone proven otherwise? I mean, why pay for something you can get for free?

Don’t get me wrong. I love the idea that people who use Spotify are likely to purchase the music they hear on the service. But supporters of illegal filesharing make the same sorts of claims, and I think they’re lying. “If I hear something I like, I buy it.” Who actually does that?

Either way, this conversation is irrelevant to the argument I tried to make. Spotify isn’t saying “our service will lead people to buy the music they listen to.” They’re saying “our service pays artists outright” and the implication is that a person listening to a track on Spotify is generating real revenue for the recording artist. This is not true, and, almost a year later, I have yet to see any data that could change my mind.

Beyond this one point, I think Spotify is fantastic, and I use it every day regardless.

So one song sold on eMusic equals approx. 100 plays on Spotify (or 200 on iTunes). I’ve gone through my old iPhone to see how many plays they got over the approx. 2 years I owned that phone. Some tracks I paid for got over 1000 plays. That means that Spotify per listen pays out 10 times more than eMusic per listen and 5 times more than iTunes. If Spotify is “not much better than piracy,” then eMusic and iTunes are WORSE than not much better than piracy.

Your math is wildly wrong. eMusic pays less per purchase than iTunes, and 200 iTunes purchases would generate over $150 for an independent artist. Did you mean something else? Please check your math and try again.

You all realize this was unavoidable, right? Single streams SHOULD be worth less than a full blown mp3. If people want a single stream, they go to youtube, where nothing goes to the artist. Spotify put out a concept that was destined to come.

The average joe on spotify will listen to the same playlist two hundred times, easily. Every day at work, ya know? People listen to the same crap over and over. in the end it works out to the same as purchasing the music. Independent artists have surged since file sharing. Who can argue any of this? We live in a different world.an amazing new and fairer world.

I have a question though, how many times do I have to thumbs-down a song before spotify takes the hint?

This is an old post, so you might not be paying attention to it anymore, and that’s fine. I came across your site when a friend recommended your post on Blurred Lines (which was an excellent explanation of what I had been trying to explain to non-musicians). I think you have the wrong cognate here. Spotify is radio. I use it to hear things I haven’t heard before, that I don’t own. I have my 80 gigs of music I’ve bought, and they’re all digitized. (I’m old; I like having a CD.)

But radio in my town is terrible. I have one rock station, and it’s pretty awful, and one decent jazz/blues station that focuses on the classics. So I use Spotify and web sites to introduce me to new music. This is a function that used to be served by radio. “Here’s the new one from…” Spotify and Rhapsody fill that void for me, playing songs I don’t know and giving me new artists to pursue.

It’s far from perfect. Because it tailors it to my other choices, I end up with things that sound too much the same, and it can take some time for a new sound to penetrate my hearing. But it’s still better than playing “Kind of Blue” or “Romantic Warrior” (to name two of my favorite records) for the millionth time.

But much like radio, the royalties involved are infinitesimal. In the bad old days, when I was recording, you got 4 cents, split between the band, the writer (which was the band) and the producer. Worse, it was a single time play. Because the radio bandwidth was a gatekeeper, if my song was playing, yours wasn’t. Spotify allows the song to be streamed not the one time, but simultaneously to a full user base.

Radio and spotify were never going to be the revenue stream for a musician. That was always going to come through sales. The sad thing now is that people hear a song and buy that song. I admit that, being old, I’ll never understand that. I hear a song I like and buy an album. It rarely steers me wrong, and when it does, I chalk it up to experience. But because it’s only one song being bought, the royalties from the song being played don’t translate to a revenue stream the way that a radio play leading to an album sale do.

It’s not that I disagree with you. I don’t. But I think your comparison is the wrong one. In the meantime, thank you for a great couple of articles.