This is a strange thing to write about, but an interview with Quincy Jones was published yesterday in which Quincy Jones repeatedly referred to Giant Steps, and at least one other John Coltrane recording, as being “12-tone.”

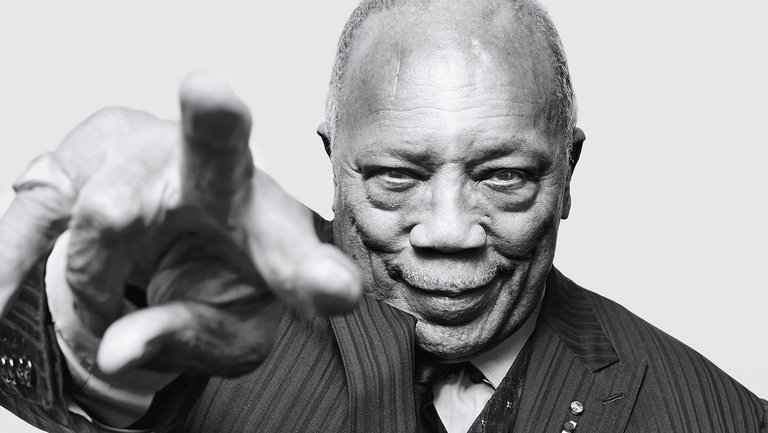

I’d put Quincy Jones near the top or at the top of any list of greatest record producers. And he’s not just a great record producer, he’s also an accomplished arranger whose best work is legendary. He deserves every superlative he receives.

But Giant Steps is not 12-tone, not by any definition of the term. Quincy Jones is very wrong about this. And I have a feeling that some people who read that interview are going to start claiming that Giant Steps is a 12-tone composition without knowing what that means, so I want to set the record straight.

Here are explanations of some basic terms that I’ll be using. I’ve put important terms in bold, and I encourage you to look them up. The free E-Book Understanding Basic Music Theory might be a good place to start.

Tonal (pronounced toe-null) refers to music where one note and chord is the tonal center at any given time. Understanding Basic Music Theory describes the tonal center this way:

Think of a very familiar tune, perhaps “Row, Row, Row your Boat” or “Happy Birthday to You.” Imagine how frustrating it would be to end that tune without singing the last note or playing the final chord. If you did this, most people would be so dissatisfied that they might supply that last note for you. That note is the tonal center of the tune, and without it, there is a feeling that the song has not reached its proper resting place.

The tonal center of a piece of music, and the scale based on that tonal center, are frequently referred to as the key of the music, e.g. “the key of C.” All of the notes and chords in a piece of tonal music operate based on their musical relationship to their tonal center. The tonal center can shift throughout a piece of music (e.g. there can be key changes,) but as long as there is one specific tonal center or key at any given time in a piece of music, this piece of music is tonal.

One way to know if something is tonal is if at any point you can say “This is in the key of _.” For example: Treasure by Bruno Mars is in the key of Eb major. How do we know this? Our ear hears Eb as the tonal center, the melody is based in the Eb major scale, and all of the chords operate in ways that lead towards or away from Eb major. (Bonus points if you know why I picked this song as the example.)

Functional Harmony refers the way that chords operate in relation to one another in a piece of tonal music. If you are learning to play songs on the guitar, you are probably getting used to playing certain chords together. If you’ve been playing songs in the key of G, for example, you’ve probably noticed that the G chord feels like the “home base” chord of those songs. Music Theorists would describe this by saying that the G chord functions as the tonal center or the tonic in the key of G. You’ve probably also noticed that the D, D7, C, E minor and A minor chords tend to appear frequently, and that they sound pleasing in different ways as they move towards and away from each other. Music theorists would say that these chords all have a certain function in the key of G. This, on a simple level, describes functional harmony. In another key, these individual chords might sound out of place, or have totally different roles to play. In the key of Eb, for example, the D7 chord sounds and functions much differently than it does in the key of G.

Modal refers to a piece of music or a performance that is based in specific collections of notes but where the harmony does not operate in a functional way. The word mode refers to these collections of pitches. An example of a mode is D Lydian. The difference between a scale and a mode is subtle and debatable; any scale can be a mode, but you generally only refer to a mode when you’re talking about a piece of music that does not have functional harmonic motion. Many musical traditions from around the world are rooted in modes, and it is not rare for pop songs and jazz compositions to be partially or entirely modal. The Beatles, for example, recorded a few songs that could be described as entirely modal; Tomorrow Never Knows is an example of this.

Virtually all of the music that you hear on a day-to-day basis is either tonal or modal, and it is not uncommon for a songs or compositions to have both modal and functional elements.

Atonal (pronounced ey-tonal) describes any music that is purposefully written or performed in a way that avoids any sense of a tonal center, and this excludes both tonal and modal music. Atonal music can have melodies and harmonies, but the melodies are not in a “key” nor a “mode,” and the harmonies do not function as they do in tonal music. These days, atonality is extremely rare outside of specific settings, but for several decades in the early- and mid-20th century, atonality was a dominant force in what we broadly call “Classical” music.

Free Improvisation or Free Jazz can refer to an improvised musical performance without any predetermined adherence to rules like chords, scales, forms, etc. It can also refer to an improvised performance that has a few guidelines in place, but where most of the direction of the improvisation is left up to the performers, who are free to take things in almost any direction. Free Jazz performances are sometimes atonal or at least not consciously tonal, and sometimes they’re not, and you can’t really put “Free Jazz” in any sort of box, because it’s free, baby. No rules here my man.

And the most important definition:

12-tone refers to a specific approach to composing and performing atonal music where all twelve notes of the equal-tempered chromatic scale are given equal value throughout a composition or performance. In a pure 12-tone piece of music, all twelve notes of the chromatic scale are placed into a unique order, called a tone row, and the relationships of the pitches in that row (and permutations of that row) form the backbone of the piece of music. There is no key or tonality in 12-tone music, nor are there functional chords like you find in tonal music. In fact, keys and functional harmony are explicitly avoided in 12-tone music.

The general consensus is that the first fully 12-tone piece of music was Arnold Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano, Op. 25, composed between 1913 and 1915:

(I did not make this video)

Because 12-tone music is purposefully written in a way that avoids tonality, and because 12-tone composers also frequently try to break other conventions in their compositions, some listeners might assume that 12-tone music is “random.” This is generally not true; while it is possible to build a row using random numbers, 12-tone music is not random; it’s highly structured, and is frequently structured to an obsessive degree. Whether it is listenable or not is up to the listener.

This all leads us to the question at the heart of this article: Is Giant Steps 12-tone? No, it does not fit the definition of 12-tone at all.

John Coltrane, more than any other recording artist that I know of from his era, pushed the limits of functional harmony with his compositions, and in this way he does have something in common with 12-tone composers. His compositions, especially those from the late 1950s, frequently feature highly sophisticated chord substitutions, multiple tonal centers that shift rapidly, and strings of functional chords that travel between several keys before arriving at their target chord. The earliest recorded example of all of this is probably Moment’s Notice, written and recorded in 1957.

(I did not make this video. It is the best I could find, but it is transposed to Bb tuning and the transcription occasionally does not match the audio.)

The unprecedented harmonic complexity of Coltrane’s music from this era, coupled with the fact that it was frequently performed and improvised over at breakneck speed, has given John Coltrane a nearly godlike reputation among many musicians. Giant Steps, the composition that brought us all here, is the most well-known and celebrated example of Coltrane’s approach to harmony, so it makes sense that it’s the composition that Quincy Jones referenced in the interview.

(I did not make this video, and I am a huge fan of this video and whoever made it.)

Giant Steps is a brilliant, beautiful, complex and highly structured piece of music, but it is not 12-tone. For a piece of music to be 12-tone, by definition, it should be written in a way where all 12 notes of the chromatic scale have the same priority throughout the piece, and there should be no tonality, no sense of any tonal center, nor any functional chord motion.

Giant Steps does not fit this definition at all, and I can feel what some of you are thinking: If Giant Steps is not 12-tone, what is it?

The harmony of Giant Steps travels through three specific tonal centers – B, G and Eb – but the common tones in the melody connect these tonal centers in a way that makes the composition feel very natural. Most people consider these three tonal centers to have equal status, but I’ve heard someone argue convincingly that it’s actually in the key of Eb, with those other tonal centers being functional within the key of Eb. No matter which way you look at it, Giant Steps travels through three keys and the movement between these keys is functional, so, by definition, it is not 12-tone. Remember: 12-tone music is rooted in a technique where the goal is to explicitly avoid functional harmony, key centers, and tonality. Unless I’m completely missing something, there is no way to even entertain the idea that Giant Steps is 12-tone.

Quincy Jones also mentions Ascension as an example of Coltrane doing 12-tone music. Ascension is a completely different story than Giant Steps, but it’s also not 12-tone, at least not to my knowledge.

A little history about Ascension: As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, Coltrane’s music became more and more spiritual and his recordings became more and more rooted in modal music. From what I’ve read and heard, his live performances became increasingly characterized by long, passionate improvisations over simpler harmonic structures. And when I say “long,” these sound like they were really long. Someone told me a story – maybe Curtis Fuller? or maybe this was in a book I read? – about how they went to see the John Coltrane Quartet, left ten minutes into the first song, came back twenty minutes later, and John Coltrane was playing the same song. And over time, these performances began to descend (ascend?) into what you would call free jazz.

In terms of Coltrane’s discography, Ascension marks the point where he went full-on free jazz, and it was a major departure even from his more adventurous quartet recordings from the 1960s. It features a huge band: two trumpet players, five saxophone players, two bassists, a pianist, and a drummer, and the recording alternates between sections where everyone is freely improvising at the same time, and sections where the individual musicians perform solo improvisations supported by the rhythm section. The album consists of one 39-minute performance spread out across the two sides of the record.

Ascension probably sounds chaotic even to the most seasoned listener, but it is ultimately a modal composition, at least to my ear. It opens with a repeated five-note melody that implies an Eb minor scale, and after a short time, this introductory section proves to be rooted in Bb harmonic minor. Being in a definable mode with an identifiable tonal center means that this section can not be an example of 12-tone music. Things get dense pretty quickly, and there are atonal choices made by the musicians in this opening section, but everything seems rooted in the Bb minor scale, with the notes Bb, Db and Eb being the predominant notes played.

At the 1:48 mark, there is a clear harmonic shift to D Phrygian, with the bass and piano clearly indicating this new mode, and the horn players clearly improvising in a way that is rooted in the mode of D Phrygian. At the 2:25 mark, there’s another clear shift to what sounds like F phrygian, but at this point many of the musicians are no longer tied to the harmonies implied by the core group of Jimmy Garrison, Coltrane, and McCoy Tyner, so there’s probably other ways to describe this section. There sounds like there may be another harmonic shift at 3:05 to C Phyrigian, and everyone seems to maybe coalesce around this mode for a moment, but it seems to devolve back to an F phyrigian-ish sort of thing before the horn chaos melts away and Coltrane takes the first solo at around 4:04. The recording continues from there.

I may be wrong about the specific modes that I’m hearing in Ascension, but there are definitely modes going on, and the band all shifts together from one mode to the next. I will admit I have never transcribed or studied a transcription for this piece of music, so I can’t for certain tell you that these performers are not using a 12-tone row to guide or ground their improvisations at some point. But knowing what I know about this piece of music, and about the musicians involved, and what I’ve heard, and the context surrounding this recording, Ascension is a free improvisation based in a series of modes. The piano and bass are grounded in identifiable modes, and the horn players improvise in ways that imply that they’re rooted in modes. It’s passionate and wild – I hear occasional shouting deep in the background when I listen with my good headphones – and frequently dissonant; The chaos probably comes across as random to most listeners, but this should not be confused with it being 12-tone.

If I am wrong, please let me know.

In the article, Quincy Jones mentions that Ascension was influenced by Alban Berg, a prominent 12-tone composer, but I can’t find any evidence of this. He mentions that Coltrane brought a certain music theory book around with him everywhere he went, but this can’t be taken as evidence that Coltrane was stealing his ideas from that book. If I’m biologist doing groundbreaking work in biology, and I’m known to carry around a physics book with me, that doesn’t mean I’m actually doing physics. So I don’t know where Quincy Jones got the idea that Ascension is an example of 12-tone music. Maybe Quincy Jones is using the term 12-tone as a metaphor, the same way you might say “he’s playing 3-dimensional chess” when someone is multiple steps ahead of everyone else.

Again, if I am wrong, please let me know.

To conclude: Giant Steps has three tonal centers, functional harmonic motion, and a melody that favors certain pitches over others. Therefore, it is not a 12-tone composition.

10 replies on “Why Giant Steps is not 12-tone”

Very interesting article, and I totally agree. I read the Quincy Jones article, and stopped to google “Giant Steps 12 tone” hoping it was actually true. It’s clearly not, but it wouldn’t surprise me if the term “12 tone” is used wrongly a lot.

Here’s a thought, though: Could he be talking about the fact that the root, third, fifth and seventh of the chords (and the melody, for that matter) cover all twelve notes in the first four bar, and then again the four next? Basically that the main frase cover all twelve notes. Still not 12 tone, but I can understand people misunderstanding the term.

Covering all twelve notes in a short phrase is not that uncommon if you include chords and different extensions, but here they are covered by very straight forward four tone chords.

Just a thought.

Thanks for a great article!

Interesting! Yeah, that could be evidence of 12-tone influence.

Thank you for clarifying this. I found myself questioning my previous knowledge of giant steps reading Q’s interview. Gave him the benefit of the doubt, but had to conclude it is not correct. I had always thought giant steps originated from:

– the B section of Have You Met Miss Jones

– and an amalgam of other things like Slonimsky’s book — coltrane did work out of that but also worked with a lot of his own variations ideas and ideas circulating the tribes he was a part of; like, experiments of cutting the tonal spectrum into 3 equal parts, it’s relation to the golden mean/golden ratio, etc.

Ascension is an elusive one. I can add that having specifically asked one of the performers who played on the recording of Ascension what they were looking at on that session, he said Coltrane did indeed give the musicians notated tone rows to derive their parts from. However, in his words, regarding that approach to music they were developing at that time, it was “every man for himself” once the music started. Sonically and literally, it would probably be better termed “chromatic saturation” or heterophony mixed with atonality or something, however I can say tone rows were involved and aided Coltrane in creating that recording. The result seems more like saturation to me than “12 tone” which seems like to broad/general term to describe such a specific thing like Ascension. It’s like categorizing a translucent aqua color as blue.

The Berg stuff could be true. Judging from the innumerable other inaccuracies in Q’s interview, I think Berg’s influence could be possible, but at least in my experiences Wozzeck is one of those pieces that “trendy” people through around in LA to sound schooled. I’m certain Coltrane knew of Berg, but I’m fairly certain, the story of Coltrane’s influence I think is a bit deeper than that. Berg is probably not the only influence or the main influence. I think likening an entire recording to one influence is a bit ambitious to begin with also. Again, this is what I was told by someone who played on Ascension, but Luigi Nono and Luigi Dallapiccola were two composers who’s music was circulating heavily through Coltrane’s circles around the time of Ascension. Gunther Schuller was another I remember being mentioned…he’d come to shows and transcribe lines as he was listening to the band apparently. There was a whole lot of obscure avante garde classical stuff circulating among those musicians at that time. The Jazz circles seem to never get enough credit for how unbelievably committed they were to staying at the cutting edge of music. They were sought out the most sophisticated approaches around at the time. Frankly hearing about the juxtaposition of their scarce lack of resources with their impeccable aptitude and taste still boggles my mind. Some of them had Julliard level classical training, others learned on their own, they all were soldiers of the classical craft of music though…it’s hard to pin point every little detail and influence, I would say though that they were probably listening to even more out stuff than the music they were making. Charlie Parker supposedly listened to Varese…ended up making lines that sound kinda like romantic composers like Strauss…

Also, Coltrane did lift things from time to time…impressions (1963) was lifted from Ahmad jamal’s pavane (1955) which was a treatment of Morton Gould’s Pavane from American Symphonette No. 2. (1939). Maybe one day we will learn if there are other tunes in Coltrane’s oeuvre that have sections lifted…

Oh wow, I had never heard Pavanne before. Yea that’s pretty much lifted, isn’t it?

Who did you speak to that played on Ascension? Is there anything I can find online about the tone rows used in Ascension?

Thank you for this entry, Dan. During my time as a jazz dilettante (ranging mostly from college in the late 1980s, maybe a little before when I thought Dire Straits qualified as jazz), I have frequently seen musicians and music writers marvel at the dense chord changes in “Giant Steps”. More recently, I have even heard some criticism of Coltrane for being unfair to Tommy Flanagan in handing him the piece’s complex chord changes only hours before their studio date. Through this thirty-odd years of fandom, however, I have never heard anyone describe “Giant Steps” as a 12-tone piece, or hint of any debt Coltrane owed to Schoenberg. To the casual ear, “Giant Steps” does sound ultimately tonal, and the animated score you link to would seem to support this.

Like you, I have a great respect for Quincy Jones; at the peak of his prowess, he probably knew as much about jazz and pop music as anyone alive. On the other hand, I have also known a great many men whose temperament grew a bit gnarled as the years went by. The tenor or Jones’ recent interview, which also touches on more salacious topics like a physical relationship between Marlon Brando and Richard Pryor, smacks more of octagenarian grumpiness than sage wisdom – though, as a harmonica player, I did appreciate his kind words about Toots Thielemans, even at Jimi Hendrix’s expense. It seems that Jones was more interested in being provocative than in being right.

You are not wrong, but neither is Quincy. He is using the term, “12 tone,” in a generic sense. Jazz composers took the idea of the tone row and grafted it on to functional harmony. Check for instance Bill Evans’ Twelve Tone Tunes. In these, Evans uses the tone row as the basis for his melody — the underlying harmony has little to do with serialism. If you combine the three key centres in Giant Steps, all twelve tones are accounted for, but there is no evidence of a row in the melody or the improvisations. Composers like Babbitt were really adept at disguising the row through the use of set theory, but they also repeated notes, something that was considered a violation of the rules early on. Ergo, perhaps twelve-tone technique should not be viewed as an immutable and unchanging set of rules, but as something that can be added to a vast compositional set of tools.

Quincy doesn’t really say “Ascension” is twelve-tone. You are right it is highly organized through motives and key/modal centres.

You are correct that Quincy doesn’t really say “Ascension” is twelve-tone. This was a misreading on my part.

But he does say “‘Giant Steps’ is twelve-tone,” and twelve-tone music is a specific thing. The avoidance of tonality and functional harmonic motion is one of the fundamental goals of twelve-tone music — at least according to my understanding of that term and my academic training as a composer.

This being said, I’m not a purist for rules in a day-to-day sense, so I don’t want to come across like I’m making an argument that I am not making. You can do whatever you want. Any combination of ideas can inspire the music you make. But a quote like “‘Giant Steps’ is twelve-tone” is misleading, and could confuse people.

Great article.

Dan, what’s interesting with Giant Steps is that the three key centers make an augmented Triad and are equidistant which makes interesting sounding relationships as you play through it. If you play though the song in 12 keys, it becomes even clearer.

Notice that Trane uses a similar Major 3rd key center relationship in Lazybird in the A section where you’re in G Major and Eb Major. The walkdown in Giant Steps also ties into Countdown and of course “Satellite” which is How High The Moon with Countdown/Giant Steps harmony layered over it. What makes this interesting is using the fifth of the dominant chord in Satellite just as in Giant Steps to make a whole tone descending bass line in counterpoint to the melody.

These same devices are used in Body And Soul, 26-2 (Confirmation with Countdown/Giant Steps layered). I find it interesting that he goes to minor 3 relationships for key centers in Central Park West, so those all spell out a diminished 7th chord. That has it’s own unique properties when in those keys are played together in a single song. 4 major triads a minor 3rd apart. Auxiliary diminished anyone???

When you start looking at the Coltrane Cycle of 4ths(5ths) he gave to Yusef Lateef and analyze the key groupings, it all starts to come together. He was trying to get to the point where the only possibility is true freedom and atonality. This is all in the spiritual pursuit of music.